Family and Early Life

Boshi was born in Bishnupur in Bankura district of Bengal in 1887. Bishnupur, despite being a small town, was of considerable historical and cultural importance since the fourteenth century, when it had come under the rule of the Malla dynasty. There were beautiful terracotta temples in the area that still attract tourist attraction.

Boshi’s father Rameshwar Sen was a mathematician who was also well-versed in Sanskrit scholarship. Ramehwar Sen was a protégé of Bhudev Mukhopadhyay, a leading educationist and academic administrator in Bengal, who had been conferred with the ‘Companion of the Indian Empire’ honour. During his University days, Rameshwar had authored a political satire in Bengali which led to his rustication from the University. He, subsequently, managed to graduate as a private candidate. Thereafter, he got recruited as a Deputy Inspector for Schools in the Provincial Education Service. Those were the days when opening of new schools based on modernised curricula had caught great momentum under the efforts of the redoubtable Ishwarchandra Bandyopadhyay, known by his honorific – Vidyasagar, whom the Government had entrusted this program with. Rameshwar Sen, who soon became Inspector of Schools opened many new institutions in the rural areas and small towns of the Burdwan district. He had a large family of eight children. While on an official tour he fell ill, and on arrival at his home, passed away due to pneumonia at the age of 52. At that time Boshi was just twelve years old.

Among Rameshwar’s children – five sons and three daughters – it was only Boshi who had a serious temperament for studies and his father too had expected a lot from him. Not feeling an environment conducive to studies at his home, Boshi relocated to the house of one of his married elder sisters in Ranchi and completed his schooling there. There were also breaks in his studies but as he was strongly determined not to give up education, he shifted to Calcutta and enrolled in the prestigious St Xavier’s College in Science stream.

At St Xavier’s College Calcutta

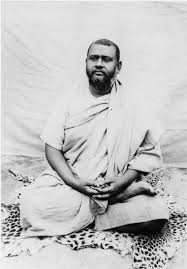

This college which even at present ranks among the finest colleges in India was founded by Belgian priest Henri Depelchin belonging to the Jesuit (S.J.) Order. Almost from its beginning, the college had an atmosphere of science which was pioneered by the iconic teacher Eugene Lafont. This missionary-teacher was not afraid of science disrupting any long-held creeds. In fact he set up a science laboratory at the St. Xavier’s College and built a culture of scientific inquiry and experimentation among the students. Along with Dr Mahendranath Sarkar, a renowned medical doctor of that time, who also had the rare privilege of serving and attending to Sri Ramakrishna Paramhansa during the latter’s last illness in 1885-86, Lafont helped found the ‘Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science’ in Calcutta. The impact of this institution, now unfortunately known only to a few, was so high that it was at its laboratory where many famed scientists, for decades to follow, delved into experimentally working out and polishing their scientific theories. This illustrious set included a Tamilian serving in the Indian Finance Service in Calcutta, C.V. Raman whose experiments at the institute, conducted during evening hours, were to eventually fetch him the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1930. The St Xavier’s College and Lafont groomed several pioneering Indian scientists, foremost of them being Jagadish Chandra Bose, who was to play a very important role in Boshi Sen’s life.

It was during Boshi’s years at the St Xavier’s College that a friend took him to visit Belur Math, the chief base of the Ramakrishna Order across the river from Calcutta. He came in touch with Swami Sadananda (Gupta Maharaj) who had the historical distinction of being the first monastic disciple of Swami Vivekananda. Through this circle he also came in touch with the fiery Scottish-Irish disciple of Vivekananda, Sister Nivedita, born Margaret Noble, who had at her Guru’s call shifted to India in 1898 and continued to work for the country in the years following Vivekananda’s death in 1902.

Nivedita had been particularly close to Sadananda, who was a companion and main helper to her during her lecture tours in different parts of the country. The two were also close collaborators in many relief programs inspired by their Master, Swami Vivekananda, like the Plague Relief of 1899 when both risked their lives serving the diseased. Sadananda and Nivedita organised bands of cleaners and sweepers, taking huge risks upon themselves, but always leading from the front.

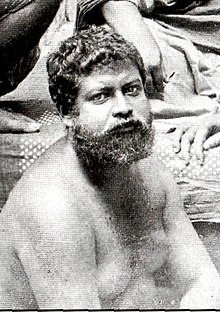

Swami Sadananda had been a young station-master at Hathras station (near Agra) when Swami Vivekananda, then aged 25, and still an unknown wandering monk, was one day sitting at the railway platform. The station-master, without even much conversation was captivated by this extraordinary personality and the following day gave up his home and career for good, following this monk in his wanderings, indeed for rest of his life. He accompanied Vivekananda in the Himalayas and since he was not habituated to such rigours of wandering life, it was the Guru who often served the disciple, carrying the latter’s belongings as well as shoes on his head. Vivekananda imbued Sadananda’a entire being with his great teaching of serving ‘the Divine in Man,’ a running theme in the message that he had given to the world, and with even greater emphasis to his own countrymen. Sadananda, encouraged by Nivedita, also used to take groups of youngsters on excursions to various parts of India, particularly historical and pilgrim-sites in northern India, with the aim of sensitising them to the history and culture of the country and instilling in them a sense of national pride.

Nivedita herself, worked and travelled like a whirlwind – she had been an educationist, worker for women’s causes, working to awaken youth and social and political actors towards a sense of Indian nationhood which was at that time rather inchoate, helping the cause of promotion of Indian science with her efforts with J.C. Bose and the establishment of the Tata Institute (later known as the Indian Institute of Science at Bangalore) and energising and sensitising young artists to recapture and root themselves in an Indian tradition of art – in this enterprise she was a collaborator to figures like E.B. Havell, Abanindranath Tagore, and a mentor to great future stalwarts like Nandalal Bose. The array of Nivedita’s activities, all directed to the one mission of serving India, was staggeringly wide.

As a result of his labours with no attention to himself, Sadananda’s health had rapidly declined and soon he was bedridden. The Ramakrishna Mission itself was greatly resource-deficient and there were no facilities or provisions for proper care of ailing monks. Therefore, Nivedita rented a house in front of her own house (16 Bosepara Lane, now a museum dedicated to her memory) in Bagh Bazar area of North Calcutta and requested Boshi to live there for serving and attending to the ailing monk. At this behest, Boshi and his younger brother moved into the house (8, Bosepara Lane) and they devotedly served the Swami. They helped him with his daily ablutions, cooked and fed him, and attended to his smallest requirements. While doing all this, Boshi continued to attend the College during the day hours. Due to their devoted service they were known as ‘Sadananda’s dogs’ in the Ramakrishna Order’s monastic and devotee circles.

Sadananda spoke to Boshi primarily of his Guru, Vivekananda. That led to Boshi’s mind being centred on Vivekananda for rest of his life. Sadananda could be very harsh in scolding young Boshi and he unfailingly pointed out smallest of mistakes. He said he did not have the time to be sweet. ‘I can only do one thing for you,’ he used to say. ‘I can take you to Swamiji.’ And this was a greater assurance that Boshi could have ever asked for. Boshi served Swami Sadananda for more than a year till the latter’s death in 1911.

Even though Boshi saw Sadananda as his Guru, he never received a formal ‘Mantra-Diksha’ from him, in the way a disciple usually receives from the Guru. Once, after the Swami had passed away, Boshi was visiting Udbodhan, the publication centre of the Order in Bagh Bazar area of Kolkata. It was there that Holy Mother Sarada Devi lived then under the care of Swami Saradananda, a direct disciple of Sri Ramakrishna. Swami Saradananda suggested to Boshi to request the Mother for ‘Mantra-Diksha.’ But the Holy Mother told Boshi that he did not need any formal ‘Diksha.’ Thus, Boshi was convinced that whatever resource for spiritual life he had needed had already been given to him by his Swami Sadananda, whom he considered his Guru for whole of his life.

Boshi was very active in the Ramakrishna Order circles. He knew several direct disciples of Sri Ramakrishna and had the great privilege of serving the first President of Ramakrishna Mission, Swami Brahmananda, who was known as the ‘Manasputra’ (spiritual son) of Sri Ramakrishna. He often gave him a massage (he was adept at that having learnt it from Swami Sadananda) and a shave. He also used to fix a hookah smoke for the Swami with meticulous effort. Once the Swami was so joyful at the quality of preparation that he remarked to Boshi, ‘Another such preparation and I shall gives you Sanyasa’ – it is to be noted that eager seekers found it very difficult to get even ‘Mantra-Diksha’ from the Swami, let alone the vows of Sanyasa. He visited him till the great Swami’s last days. Swami Brahmananda, had a nature of eagerly wanting to know of latest developments in science and Boshi used to recount to him some such things Once in a serious mood he told Boshi never to give up science and that the latter would achieve everything in his life through its pursuit. This became an article of faith with Boshi for rest of his life.

Recovering from the blow that Swami Sadananda’s departure had caused him, Boshi did not know a similar jolt was to be faced soon. Within a few months of Sadananda’s passing away, Boshi lost his major mentor and well-wisher Sister Nivedita, who, just a couple of weeks short of 44, suddenly shed her mortal coil in Darjeeling.

In the short span he knew Nivedita, the latter had already influenced Boshi’s life in a very significant way. She had connected him with his spiritual Guru, helped imbue him with the spirit of Vivekananda, and gave a very important turn to his future by help propel him in a career of science. This last great help, she did by introducing him to her close friend and associate Jagadish Chandra Bose. She requested the great pioneering experimental scientist of modern India to take Boshi as his apprentice. This is how Nivedita had sown the seeds for Boshi’s future career as a scientist.

Boshi joined J.C. Bose at a stipend of Rs Twenty and his next twelve years were devoted to learn from this great Master – his Guru in Science, as he always said. About Nivedita, Boshi would later feelingly say, ‘I owe my science to Nivedita. It was she who placed me under Sir J.C. Bose. It is difficult for me to express what I feel about her. In my own little ways I try to express in life some of the dynamic ideas she used to radiate.’

Under the tutelage of Sir Jagdish Bose

By that time, J.C. Bose was already a towering figure in the world of science. Bose too had studied at St Xavier’s College Calcutta after which he took degrees from Christ College of Cambridge University and subsequently from London University. Upon return to India, he became a Professor in Physics at the prestigious Presidency College in Calcutta. At the Presidency College, he set up a Laboratory where Boshi joined him in 1911 and continued to work for the following 12 years. All through these years, Boshi never took a single day off, working all seven days. He often took meals at the Bose house, and besides assisting in research did several acts of personal service to Bose like even managing the scientist’s laundry.

In 1914 Boshi accompanied Bose on a tour to the West and witnessed his master deliver lectures in the highest echelons of modern science – at places like the Royal Institution, Cambridge University, Vienna, and Paris among several others venues. Boshi too got opportunity to meet eminent personalities like Lord Rayleigh, George Bernard Shaw and Sir Francis Darwin. He accompanied Bose to meet Gopalkrishna Gokhale at the National Liberal Club in London, where Gokhale introduced them to a rather unimpressive looking younger person referring to him as the future leader of India. This was none other than M.K. Gandhi who had already created quite a stir in South Africa and was about to return to his homeland. In the first meeting Boshi was deceived by Gandhi’s simple appearance and for one who was used to fiery and flamboyant political personalities from Bengal like Surendanath Banerjee, Bipinchandra Pal, and Aurobindo Ghose, he thought Gokhale was being just too optimist. In his later life Boshi regretted that he did not have a chance to tell Gokhale of how correct his prophecy was.

But 1914 was not a good time for world travel. When the two were on their continental tour, the great War broke out in Europe and it became impossible for them to return through the regular route. So they extended their tour across the Atlantic, where Bose lectured at the Columbia University, the American philosophical Society, New York Academy of Sciences, the Smithsonian Institution, and the State Department. Bose’s lecturers were attended by eminent persons like Nikola Tesla, Percival Lowell and Graham Bell.

Upon returning to India, J.C. Bose fulfilled his dream of starting his own institution for research and experimental science. The Bose Institute was opened in 1917 with its logo designed by Nandalal Bose and the Institute’s anthem composed by the scientist’s closest friend, Rabindranath Tagore. At the Institute, Boshi worked with his master on advanced research themes like simultaneous determination of excitation by mechanical and electrical methods, effect of Carbon Dioxide on mechanical and electrical pulsations of desmodium gyrans, transmission of death excitation, and relation between permeability variation and plant movements. While working on these subjects, Boshi had been in contact with eminent physiologists like SH Vines, WM Baylis and Nobel Laureate AV Hill.

In 1923, Boshi was introduced to Glen Overton and his wife Marguerite who were visitors to the Bose Institute. Coming to know of their interest in exploring India at a deeper level he took them to Belur Math. At their request, he also accompanied them on a fortnightly tour to various places in the country. The Overtons were charmed by Boshi’s personality and offered to host him in America. They suggested that he take a break to visit leading American Universities and get best exposure to the latest development’s in the field of research in areas he worked and was interested in. The idea naturally excited Boshi but Sir JC Bose apparently was not very happy. He felt that Boshi was getting distracted and losing focus in his duties at the Institute. He, nevertheless, left it to Boshi to decide. Boshi sailed with the Overtons to American West Coast in March 1923.

Boshi in America – 1923

However, upon reaching America, Boshi found that due to sudden decline in their fortunes, the Overtons were not in a position to keep their promises in the way he had imagined. Realising that he should no longer depend on anyone, he reached New York and met Patrick Geddes, the great Scottish polymath, who knew him well through Bose. Geddes had at different times been a friend of Vivekananda, Nivedita, Tagore and Bose. He had also worked in India briefly in the area of town planning. With Bose he was so impressed that he authored one of the first biographies of the great scientist. Geddes, upon seeing Boshi’s predicament, introduced him to Leonard Elmhirst, an agriculture scientist from Cornell University. Elmhirst had been a friend of Tagore and had been invited by the Poet to set up a Rural Reconstruction program at Santiniketan. He was, at that time, affianced to the American millionaire Dorothy Straight, whose deceased husband Wilfred Straight, also a Cornell Professor, had been the promoter of the ‘Asia’ magazine.

Elmhirst first suggested Boshi to join him at Santiniketan and help strengthen the Science Department at the newly started Viswa Bharati University. Boshi, who had the experience of working for long years in assisting Bose, now wanted to work independently and hence declined the offer. Also, because Tagore and Bose were close friends, he thought leaving Bose Institute for Tagore’s University might possibly trigger a misreading of the situation by some people. He requested Elmhirst to sponsor equipment for setting up a small laboratory where he could work by himself, a proposal to which Elmhirst agreed.

Thus, on return to India, Boshi planned to set up a small unit at Bose Institute where he could take up independent projects. He discussed the plans with J.C. Bose, but the latter was not very receptive of this. To be fair to Bose, he perhaps thought it might be better if Boshi started on his own independent path instead of setting up a centre at the Bose Institute. Boshi, though a bit disappointed at his mentor’s response, became clear that he had to set up his lab on his own. He tendered his resignation at the Bose Institute and decided to set up a small laboratory in his kitchen at the Bosepara Lane house. Parting ways from Bose would have been painful for both but Boshi acknowledged Bose as his Guru in science and remained grateful to him all his life for what he learnt from him.

Boshi started his kitchen laboratory on 4th July 1924 (on the death anniversary of Swami Vivekananda) and named it ‘Vivekananda Laboratory’. He began to get support from friends and well-wishers like the Overtons, Elmhirst and Dorothy Straight, the famous Russian artist Nicholas Roerich, and Josephine Macleod – a close friend and devoted admirer of Vivekananda, and a great champion of the Ramakrishna Movement in its first few decades. The good word about his efforts had spread and once he also had the Governor of Bengal, Lord Lyton, as a visitor to his Kitchen Laboratory. Lord Lyton offered Boshi a government grant but the latter declined saying that he had got resources just enough for his modest requirements. One gathers that Boshi Sen was by nature more comfortable in intensive private research instead of being lured to the trappings of big-scale institutional enterprise. This trait of his nature would not change much throughout his life.

All this while, Boshi, was also engaged in service of the elders in the Ramakrishna-Vivekananda circles. He looked after Sister Christine, a German-American disciple of Vivekananda, who had joined Sister Nivedita in running the girls’ school in Bagh Bazaar and in other women’s projects. Sister Christine, born Christine Greenstidel, had first heard Vivekananda speaking in Detroit around 1894-95. She was so inspired that she then attended a retreat at the Thousand Island Park where the Swami lived for about six weeks with a dozen sincere spiritual aspirants in an intimate ambiance. The lofty teachings that flowed from Vivekananda there were captured in the book ‘Inspired Talks’ taken in notes by another American disciple. Christine’s mind was made to serve in India and after attending to some familial matters she arrived in India just after her Master had passed away. But she continued to work and serve in India.

Around the time when Boshi had set up his own Lab, Josephine MacLeod suggested to him to consider setting up a place in the more pleasant climate of the hills where she and other western devotees could also visit. Almora was an important place for the Ramakrishna Movement because of its proximity to the Advaita Ashrama at Mayavati located further upward in the same district. The town was also sanctified by three visits of Swami Vivekananda in the years 1890, 1897 and 1898, and also had an ashram started by Vivekananda’s brother-disciples, Swami Shivananda ans Swami Turiyananda. This led to the setting up of Boshi’s summer laboratory in Almora at a rented place called ‘Kundan house’ in 1926.

At this time Boshi was to meet an equally extraordinary person, perhaps even more so, something he might not have expected to happen at this stage of his life. He was to meet the American explorer, adventurist, writer, and intellectual Gertrude Emerson and in a few years from then get married to her. But who was Gertrude Emerson?

▶ Next Chapter: Gertrude Emerson : Vita Incredibili