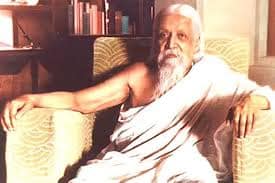

Sri Aurobindo was born in Calcutta on 15th August 1872 to Dr Krishna Dhan Ghose and Swarnalata Devi. Dr Ghose was a civil surgeon in British government service who had made up his way through difficult circumstances. Having lost his father at the age of twelve, he went, much against his family’s wish, to Calcutta Medical College and was subsequently posted in Bhagalpur. He later went to the United Kingdom to get his M.D. degree. Swarnalata, his wife, was the daughter of the famous nationalist and Brahmo leader Rajnarayan Bose. Upon his return he was posted to Rangpur (now in Bangladesh) as the civil surgeon of that district. Since the conditions in Rangpur were very unhealthy he sent his wife who was expecting the birth of their third child to a friend’s home in Calcutta. A boy was born and given the name Aurobindo.

Dr Ghose also gave the boy a middle name of Ackroyd, ‘Ackroyd’ was the family name of Annette Ackroyd, a dear friend of Dr Ghose. She was a remarkable woman, one of the early pioneers in girls’ education, who founded the Hindu Balika Vidyalaya in Calcutta (later merged into Bethune School), and had translated the Baburnama and Humayun-nama from Persian into English.

In 1877, when Aurobindo was five, Dr Ghose sent him and the two elder boys (Benoybhushan and Manmohan) to a prestigious school, Loreto House, in Darjeeling. The boys studied there for two years. But Dr Ghose was convinced that he wanted the boys to be brought up as Englishmen. He also wished that they should make it to highest possible careers available to Englishmen like the Indian Civil Service. He felt this would not be possible if the boys continued to stay in India. So, in 1879, he took the boys to England where he arranged for them to be looked after by a couple called the Drewetts in the industrial town of Manchester. Mr William Drewett, the husband, was a clergyman.

The Ghosh couple had another son born to them in England. They named hiim Barindrakumar. Leaving the the elder boys under the care of the Drewett family, Dr Ghose and his wife, along with the baby Barindra and daughter Sarojini, returned to India the following year. The three boys settled under the guardianship of the Drewetts.

Growing up with English guardians

After two years of home-schooling Benoybhushan and Manmohan were admitted to Manchester Grammar School while Aurobindo continued to be tutored at home. Mr Drewett taught him Latin and History while Mrs Drewett taught him English, Arithmetic and French. The Drewetts were a devout Christian family and even when Dr Ghose had asked them not to expose the boys to any kind of religious influences, the boys had, to some extent, soaked from the general atmosphere in the house. Sri Aurobindo later remarked, that Christianity was the only religion and the Bible only scripture with which he was acquainted in his childhood. He did read the Bible during those years, and regarded the King James’s version, published in the early seventeenth century, as a masterpiece of English prose. He also read great English poets and had a special liking for Shelly’s ‘Revolt of Islam’ though he later said it was not fully intelligible to him at that time. What appealed to his young mind was the idea of freedom from tyranny and injustice. He also liked Shelly’s ‘The Cloud’ and wrote a poem using that meter. During these years he also wrote some verse for the Fox’s family magazine.

In London

After five years of this arrangement there came a change. The Drewetts decided to migrate to Australia but they left the boys under the care of Mr Drewett’s elderly mother. The lady along with the boys moved to London where they took residence at Stephens’s Avenue. Manmohan and Aurobindo were now admitted to the prestigious St. Paul’s School as day-scholars.

The St Paul’s School had a long and rich history, much like Eton and Harrow. Founded in 1509 by John Colet it was intended to be an institution embodying the best humanistic values of European Enlightenment. Indeed the text books for the school were written by the eminent Renaissance figure Erasmus whose influence helped in shaping the renaissance spirit in Northern Europe. The School offered a number of scholarships to meritorious students and Aurobindo got one. The High Master of the institution was one Fredrick William Walker who put the institution at the top of all England schools of the time. Incidentally he had also served at the Manchester Grammar School in the past. He was known to give individualized attention to each of the students in the institution and groom them, as per their make-up to their full potential. Mr Walker initially admitted thia gifted pupil in the Fifth Form and helped him with his Greek learning. Favourably impressed with the boy’s learning aptitude he soon fast-tracked Aurobindo to the Seventh Form where most of the other boys were elder to him.

At St. Paul’s, Aurobindo acquired a fair bit of mastery over Latin and Greek, as also over English and French. In the seventh form itself he gained knowledge of the heyday of the Roman civilization by his studies of Cicero and poetry of Virgil in original Latin. He also furthered his knowledge of the Greek language and the Hellenistic culture by reading Euripides, the dramatist and Xenophon, the Philosopher-historian. He also read English and French literature and gained enough proficiency in modern European languages like German and Italian to read high literature in them.

The time at St. Paul gave Aurobindo great confidence in his abilities and helped him keep higher goals for his scholarly attainments. In the initial years the brothers occasionally went for holidays to the countryside like the St Bees and the Lake District but later had to struggle financially.

Mr Walker was a big votary of learning a language through practicing exercises in translation. His method to make his pupils acquire a fine style of English composition was to make them translate long passages from Latin and Greek into English. This method was found to be very effective and Aurobindo acquired a brilliant style of writing in English which was to be with him for whole of his life. Benefited by such methods St. Paul’s was a great nursery for many distinguished English writers during Mr Walker’s time.

Aurobindo, however, did not quite learn the sciences. In his inimitable style, he referred to this in his later life : “Not one word of Chemistry or any other damned science. My school sir, was too aristocratic for such plebeian pursuits.”

Aurobindo was an active participant in English and French debating societies and also a member of the School’s literary society. His interests were not limited to the demands of the school curriculum: he spent a fair bit of time in reading English and French literature and also wrote poetry. At St. Paul’s he also had to read the Greek New Testament, and Anglician doctrine and history of the Church of England.

It is said that many years later, during the time of Alipur conspiracy case, when Aurobindo’s name was featuring in the British press, Mr Walker, remembered him as the most intellectually gifted boy who had ever passed through his hands at St. Paul’s.

During this time the boys fell off with the elderly Mrs Brewett when her religious sensibilities were offended by a comment by Manmohan. She decided to leave the house and the boys began to manage the household affairs themselves. They did not, however, seem to miss her presence.

But the financial condition of the brothers was becoming increasingly difficult. In the initial years the brothers occasionally went for holidays to the countryside like the St Bees and the Lake District but later that came to a halt.

The remittances from Dr Ghose, earlier around three hundred and sixty pounds annually, were not regular as before and naturally the expenses of the boys had increased with their age. Because of this they had to leave the Stephen Lane dwellings. Luckily one James Cotton, brother of Henry Cotton, an ICS officer posted in India and a friend of Dr Ghose, arranged for their stay in a room at the Liberal Club in South Kensington which he managed. Benoybhushan, whose education had ended after the school, assisted Mr Cotton in petty tasks and was paid five shillings a month. The boys had to bear a poor diet. Aurobindo described the time in his words :

“During a whole year a slice or two of sandwich bread and butter and a cup of tea in the morning and in the evening a penny saveloy formed the only food.”

In December 1890, a term before completion of his stint at St Paul’s, Aurobindo appeared for the entrance to the King’s College at the Cambridge University as a classical scholar. For this he was tested with translating challenging passages from Greek and Latin to English and vice-versa. There were also tests for Classical Grammar and English composition. He topped the examination and was admitted as a Senior Classical Scholar at the King’s College winning a handsome scholarship.

In Cambridge

He joined the College in October 1890. He received eighty pounds annually as a Senior Classical Scholar and was given a lodging across the King’s Lane. Even for someone like him who had come from one of finest schools in the whole of British empire, the transition from St. Paul’s to Cambridge was quite overwhelming. He himself said that : “He who entered the University a raw student comes out of it a man and gentleman, accustomed to think of great affairs, and fit into cultivated society.”

Founded in 1441, by Henry VI, the King’s College had some of the finest buildings in England which were marvels of architecture. Its Chapel is regarded as one of the greatest examples of late Gothic English architecture and one of most beautiful buildings in England.

Referring to such an ambience Aurobindo remarked that one was privileged to move “among ancient and venerable buildings, the mere age and beauty of which are in themselves an education.”

In June 1890 when he was not even eighteen, he appeared for the qualifying examination of the Indian Civil Service. In this he took ten papers like Latin, Greek, Italian, French, English Literature, English History, English Composition, Political Economy and Mathematics. He scored record marks in Latin and Greek and secured an overall rank of eleventh among the successful candidates and now entered the probationary stage.

The ICS required a probationer to complete the Tripos within two years of the ICS qualifying examination. The Tripos, in its usual course, took three years, after which a degree was awarded. Moreoever, the probation required one to clear two periodic assessments and a final one. After successfully clearing the first and second assessment examination a candidate was to receive a stipend of seventy-five pounds each time and a hundred and fifty pounds after clearing the final examination.

In most cases students took a year of special tutorials for preparing for one of the toughest examinations in the world and many made in second or third attempts. Aurobindo could have chosen to appear for the examination after a year at the College. He would have then got his Tripos degree too which was awarded only after spending three years at the University. But it was his need for money, during those days – not just for him but his brothers too – that he appeared in the ICS straight after passing out of St. Paul’s.

So it was a considerably magnified work load for Aurobindo; not only did he have to complete the Tripos in two years instead of the customary three but also keep on clearing the periodic assessment examinations which had diverse subjects like Jurisprudence, Political Economy, and Bengali (as he was assigned the Bengal for his future service). As a Classical Scholar at King’s College he had to continue his studies in Greek and Latin. Since he has considerable mastery over this he allocated a greater part of his time to the studies of the ICS subjects. In Jurisprudence he read texts like Justinian’s Institutes and Jeremy Bentham’s ‘Theory of Legislation.’ He also had to familiarise himself Indian legal systems – both Hindoo and Moslem – that were in practice in India then. In political Economy his tutor was Neville Keynes, father of the legendary John Maynard Keynes, and he read texts from Adam Smith, David Ricardo and John Stuart Mills. In Indian history he read scholars like James Mill and other British authors who naturally interpreted Indian history to suit the colonial narrative.

At the King’s College, he met the redoubtable scholar of classical languages, Mr Oscar Browning. During this meeting Browning first asked Aurobindo whether he realised that he had successfully passed an extremely difficult examination to win the Senior Classical Scholarship. He then proceeded to tell him that in thirteen years that he had evaluated candidates for this examination, he had never come across papers as excellent as those of Aurobindo. He termed his essay as ‘wonderful.’ When he came to know of the modest lodgings where Aurobindo was then living, he lamentingly exclaimed, “We get such great minds to come here and then shut them in that box. I suppose it is to keep their pride low.”

Aurobindo’s Bengali tutor, one Mr Towers (popularly referred to as Pandit Towers) himself had a rather outdated knowledge of Bengali and had hardly any familiarity even with the works of Bankimchandra Chattopadhyay, the greatest Bengali writer of the day. Aurobindo had to make do with self-learning in Bengali as also with Sanskrit, two papers he had to clear in his ICS probationary assessment examinations For Sanskrit he tried to learn by carefully studying the ‘Nal Damayanti’ episode of the Mahabharata. This was perhaps his first attempt at learning Sanskrit. He also began to read the Upanishads in English by Max Mueller. Such was a beginning of a life-long love for sacred texts of India.

Aurobindo’s reading of great literature that had started in Manchester reached its pinnacle by the time he was leaving Cambridge. He had studied Greek masters from 750 B.C. onwards, like Homer, Euripedes, Aeschyllus, Plato and Epictetus, and great Latin writers like Cicero, Catullus and Virgil. He also reaf later writers like Dante in Italian and Racine in French among many others. Besides, though it hardly needs mentioning, he had done solid studies of English literature and had thorough knowledge of works of Shakespeare, Milton, Shelly, Keats, Wordsworth, Byron, Tennyson, Browning and many other contemporary writers of the late Nineteenth century. He continued to write poetry and many poems he wrote during this time were included in his volume’ Songs to Myrtilla’.

He was, however, not interested in sports and games and because of this he might have missed on some more experiences in Cambridge that others went through. But still, on the whole, he had a very fulfilling time there. He later referred to this :

“I think there is no student of Oxford or Cambridge who does not look back in after days on the few years of his undergraduate life as, of all the scenes he has moved in, that which calls up happiest memories.”

For some years before this, even as early as his time at St. Paul’s, a feeling was building up within him that his life was meant for a very great purpose. By his Cambridge days this feeling was raging in his mind that he had to return to India and serve the country of his birth and ancestors. His father too, by that time, felt the great misery of his countrymen under British rule, and the sentiment was being strongly reflected in his letters to his sons. At Cambridge, Aurobindo was associated with the ‘Indian Majlis’ – a forum that enabled him to get greater familiarity with the current political debates concerning India. He was also interested in the Irish struggle and admired Charles Parnell to the extent of writing a poem when the Irish leader died. After the end of his second year at Cambridge, Aurobindo became clear that his future lay in India.

He still had to decide about the ICS. Despite receiving multiple calls, he did not appear for the mandatory horse-riding test, and finally got disqualified from the service. Upon receiving the news he came home and casually remarked to his brothers that he had chucked the ICS. It was an extraordinary occurrence with hardly any precedent. A certain Subhas Bose, not born at that time, was to do this three decades later. He must have had Aurobindo’s example to inspire him.

One might ask why did Aurobindo spend time competing for the ICS when he did not finally join that service. Two reasons could possibly serve as explanations. Firstly, right from the time he was brought to England, his father kept the goal of ICS before him. He could not have disappointed him by simply not appearing in the examination, and hence letting go of that possibility prematurely. His mind was also taking time to come to a clear decision, and it was only natural that only through considerable reflection he could arrive at the firm conviction that the ICS could not be an appropriate vehicle for him to serve his countrymen. Like what was said about the ‘Holy Roman Empire,’ he possibly realised that the so-called ‘Indian Civil Service’ was neither Indian, nor civil or service. Secondly, his nature during those times was first and foremost that of a scholar and pursuing knowledge even for his ICS papers was something a person of his temperament would have enjoyed. But the later humdrum life of an administrator was not something that could have suited his temperament.

Even rejecting ICS he could have stayed in England as a poet-scholar in academic line. That was more in line with his nature than the grind of an administrative career. But even that was superseded by the need to serve people in India. And it was no ordinary notion of service. He was prepared to sacrifice his all in the process.

His mind was made up to serve India.