I

Not too many persons these days have heard of the genius of Dilipkumar Roy – a great singer, songwriter, composer, musicologist, biographer and playwright who was a giant of the artistic and intellectual firmament of the twentieth century India. Roy was one of the chief disciples of Sri Aurobindo, a very close friend of Netaji Subhaschandra Bose, and a much adored spiritual guide to many in his later life. While he was still young he met world luminaries like Romain Rolland, Bertrand Russell, Georges Duhamel, and Hermann Hesse, and had opportunities to discuss at considerable length a variety of topics with great compatriots like Mahatma Gandhi, Tagore, and of course Sri Aurobindo.

Dilip was the son of a highly illustrious father – Dwijendralal Roy, who though had received a degree in agriculture from England, eventually became known as the great dramatist and composer-songwriter in Bengali and having more than 500 compositions to his name which form an entire body of work known as ‘Dwijendra Sangeet’. Dilipkumar, born on 22nd January 1897, just a day before Subhaschandra Bose, was exposed to high ideas of art and creativity right from his childhood. His ancestry could be traced to Advaita Goswami, a great saint and follower of Sri Chaitanya. His grandfather was the Dewan of the princely state of Krishnagar and a fine classical singer himself. Dilip lost his mother when he was just 6 and his father too passed away ten years later. He was then raised in his grandfather’s house in Calcutta.

An early influence on him was that of elder cousin Nirmalendu, who intensified the spirit of devotion in him and also acted as an early mentor. In this phase Dilip read Sri Ramakrishna Kathamrita and met its chronicler – Sri Mahendranath Gupta (Sri M), and also visited the Kali Temple at Dakshineswar, where Sri Ramakrishna had spent long years.

Dilip had his early tutoring at home where he was taught English, Mathematics, History and Geography. He learnt Sanskrit by reading great Indian epics and also Bengali by reading the great literature of the day, including his father’s works.

Like his father, Dilip too joined the Presidency College in Calcutta and secured his graduate degree in Mathematics. He, thereafter, went to the Cambridge University to get a Tripos in mathematics and also, in parallel, enrolled for a degree in western music. There were some expectations of the family that he might try his hand at appearing tor the much coveted Indian Civil Service but Dilip, by then, was realising that his grand passion impelled him towards a vocation in music.

He did not complete the Tripos and went to Berlin to learn lessons in voice training and the violin, as also get exposure in German and Italian musical traditions. He learnt to speak French fluently and could handle German and Italian too to a reasonable degree. There he was exposed to the great strides the Western Classical Music had made during the preceding two centuries and got rich knowledge of masters as Beethowen, Mozart, Wagner among others. He studied under the great Hungarian musician Jukelius, who hoped that Dilip would become a great ‘Opern Sanger.’ However, Dilip had no such wish and took the trainings in western methods including the operatic tradition only to widen his musical horizons.

Dilip’s mind was made up to take up music as his life’s mission though it was, during those days, a very unconventional choice. One heard of musicians only under the patronage of royal courts and most among his family and friends found what he wished to do as rather bizarre. He was however encouraged by Romain Rolland with whom he had extensive interactions during his European sojourn and also later by Rabindranath Tagore. His close friend Subhas too, who himself had chucked away his ICS career, encouraged him thinking that Dilip through his music could intensify the country’s patriotic fervour.

Dilip returned to India in 1922 and immersed himself in deepening his knowledge of musical traditions of the land. He was very impressed by the musical expertise and musicological insight of Vishnu Narayan Bhatkande, a lawyer turned musician who was credited with writing the first modern treatise of Hindustani classical music which till then was only being communicated in an oral way through the Guru-Shishya tradition. Bhatkande had travelled all across India, and in particular, many princely states which patronised music like Baroda, Gwalior and Rampur and eventually built a theory of North Indian music in line with its ancient traditions. He was, like V.D. Paluskar, one of the pioneers in starting schools for training students in Hindustani music, again a departure from the traditional gharana system.

During the last years in the life of Dilip’s father, Dwijendralal, some misunderstandings had cropped up between Tagore and him. However, Dilip always received a lot of affection from the Poet. As early as the 1920s Tagore had invited Dilip to Professorship of music at Viswa Bharati, an offer Dilip declined. Dilip had been the Poet’s guest at Shanti Niketan on several occassions. The two also debated whether Rabindra Sangeet should be confined to standardised musical notations, or whether a performer should have freedom to interpret it in one’s own way. The Poet was in favour of standardised notations whereas DIlip thought an artist should have his interpretative freedom. However, it seems that with time Dilip saw merit in Tagore’s position.

In 1923 Dilip’s attention was drawn to Sri Aurobindo by a friend, Ronad Nixon, who later took to a life of renunciation and came to be known as Yogi Krishnaprem. Nixon had been a Royal Airforce Pilot during the great War and disillusioned by the overwhelming scientific-materialist armosphere of rge wester world relocated to India and was at that time teaching English at the Lucknow University. Nixon was of the opinion that Sri Aurobindo’s volume ‘Essays on the Gita’ surpassed any other earlier commentaries and broke new grounds by its author’s resplendent insights and Yogic intution. Encouraged by this opinion Dilip met Sri Aurobindo for the first time in 1924. However, Sri Aurobindo, seeing that Dilip was not yet fully ready to wholly take a life of Yoga did not ask him to join the Ashrama.

Between 1923 and 1927, Roy travelled across the country collecting songs and bhajans in many different Indian languages. He also studied music under great teachers like Ustad Faiyaz Khan of the Agra gharana and Ustad Abdul Kareem Khan of Kirana gharana. He documented a very large number of songs along with musical notations ensuring that they were not lost to posterity.

In 1927 Roy again travelled to the West. He had been invited to speak at many places and give lecture-demonstrations There in the Cote d’ Azur (the French Riviera) he spent some time with his European friends and met Paul Richard, author and seeker, who strongly impressed upon Dilip’s mind the greatness of Sri Aurobindo. Richard was of the opinion that in Sri Aurobindo was manifesting the world’s greatest spiritual force of the time. Dilip did not lose much time in making a final decision after that.

In 1928 when he was just 31, Dilip finally joined the Ashram of Sri Aurobindo at Pondicherry and spent more than two decades in his master’s close company till the latter passed away in 1950. He called Sri Aurobindo “one fixed star in his otherwise kaleidoscopic life.” For about eight years he did not leave the ashram. Thereafter, with his Guru’s blessings, he continued with his work in Indian music – singing, composing and collecting rare songs all over the country. He was largely responsible for collecting the songs which were used in the film ‘Mirabai’, immortalised by the voice of M.S. Subbulakshmi. Dilip also set Bankimchandra’s ‘Vande Mataram’ to a new tune and also sang this great song with Subbulakshmi. He had hoped that ‘Vande Mataram’ would become the National Anthem after indepedence ans qas disappointed when that did not happen. He also did occasional concerts and through these means raised funds for the Aurobindo Ashram. Subbulakshmi had high admiration for Dilip’s singing and said that he sung from the very depths of his inner being.

Dilip left Pondicherry in 1953 and after that again undertook a world tour. In 1959, he established the Hari Krishna Mandir in Pune along with his disciple Indira Devi. The duo also wrote an autobiographical work titled ‘Pilgrims of the stars – An autobiography of two yogis.’

Dilip was a highly prolific writer. He wrote about a hundred books in Bengali and English. He also wrote plays, among them were ones based on lives of Sri Chaitanya and Mira. He wrote reminiscenes of Subashchandra Bose both in English and Bengali. He published a biography of Atulprasad Sen, with rich discussion of Sen’s art of songwriting and music, and also one on his friend Yogi Krishnaprem, who had settled in Uttarakhand and lived a life of great austerity on high Himalayas. As far as Dilip’s contribution of collecting songs from all across the country and passing them to the next generation is concerned, his name should be written in golden letters in India’s musical tradition. He translated a large number of songs from Hindi to Bengali and English and also from Bengali to English. He set to tune many songs of Indira Devi (that were written in Hindi) and also translated them. He also sang a number of Bhajans with Indira Devi, who, it is said, wrote and sang in trance-like states. In the last phase of his life in Pune spanning two decades, Dilip only sang devotional songs.

Other than that of his father, Dilip’s renditions of Nazrul Geeti, the body of work by Kazi Nazrul Islam as well as songs of Atul Prasad Sen, have also been very popular. He also sang a number of songs of Nishikanth who too lived at the Aurobindo Ashram.

Dilip had met and sung for Gandhi several times and had interesting discussion on art and music. He first met Gandhi in 1924 when the latter was recuperating at Sasoon Hospital in Pune. Dilip approached Gandhi with some apprehensions about Mahatma’s views on art and music. However, Gandhi soon put to rest all these notions and said he did enjoy music, particularly devotional songs, immsensely. Both also thought that rich musical heritage of the country was woefully neglected in the educational institutions. Gandhi told Roy that ascetism was the greatest of all arts as it was the loftiest manifestation of beauty in daily life shorn of any artificialities and make-believes. In a Prayer Meeting in later part of 1947 where Dilip sang, Gandhi remarked that he was of the opinion that very few in the country or even the whole world equalled the singing prowess of Dilipkumar Roy.

Dilip was giving a lecture-demonstration in Calcutta University for post graduate students when the news of Gandhi’s assasination came and the meeting was dissolved and one student in the audience fainted. Dilip himself had fever later that night. Though not always agreeing with Gandhi’s views and political actions, he was always charmed by Gandhi’s disarming cheer, humour and affection. Dilip’s interactions with Gandhi and several other towering figures appear in his marvellous work ‘Among the Great.’

In his later years in Pune, Dilip was affectionately addressed as ‘Dadaji.’ He sang great Bhajans, many of which renditions have since then become classics like ‘Mohe Chakar Rakhoji’, ‘Mere Giridhar Gopal’, ‘Giridgar Aage Nachoongi’, ‘Radhey Govind bol tu mukh se’, ‘Kaisi lagi lagan’ and hundreds of other devotional songs in Hindi and Bengali.

Dilipkumar Roy passed away in 1980.

II

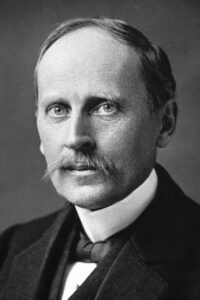

In 1920 when Dilip was still a student at Cambridge he was enthralled by reading ‘Jean Christophe’ and wrote to its author – the great French literateur and intellectual – Romain Rolland, who was then living in Switzerland. Rolland had already secured for himself a worldwide reputation having won the Nobel Prize in 1915, immediately after Tagore received the Prize in 1913 (there was no Prize given in 1914), for this monumental 10 volume work. The work was published over nearly a decade and was also seen as a vehicle for the author’s own views on art, life, and European society and politics of the day. Rolland was also known for his critique of aggressive nationalism and advocacy for democratization of the arts, expressed in his works dealing with People’s Theatre.

Rolland had been a Professor of history of music at the great French university of Sorbonne, a position he quit to engage fulltime in literature. He also shifted to Switzerland, not agreeing with his country’s nationalist position. He had also published a notable biography of Beethowen in 1903 and was, in some ways, to model his Jean Christophe, on the German genius. He was hugely influenced by Indian thought – Vedanta and not just Buddhist philosophy, which was most Westerners knew about India then – and was to later write biographies of great Indian spiritual masters – Sri Ramakrishna and Swami Vivekananda. He was also inspired by his exact contemporaries Gandhi, Tagore and Sri Aurobindo. He published a book on Gandhi in 1924 and wrote of contemporary India in his 1927 work ‘L’Inde Vivante’ (Living India.)

Of Tagore and Gandhi he wrote, “Oh Tagore, Oh Gandhi, rivers of India, who like the Indus and the Ganges, encircle in your double embrance the east and the west – the latter, Mahatma, master of self-sacrifice and heroic action – the former, a vast dream of light – both issuing from God Himself, on this world tilled by the ploughshare of Hate.”

In Rolland appeared a great force attempting to unite the Orient and the Occident. In a letter to Tagore in 1923, Rolland wrote that “the union of Europe and Asia must be, in centuries to come, the most noble task of mankind. As for myself, India from now on is not a foreign land, she is the greatest of all countries, the ancient country from which once I came. I find her again deep inside me.” Rolland very keenly wished to visit India. This, however, remained an unfulfilled wish.

Upon receiving Dilip’s letter, Rolland wrote back, inviting him to his home in a little Swiss village of Schoeneck. As one of the most prominent voices in Europe in the inter-war years Rolland felt that the Orient had the Light which could show the whole world path out of darkness.

In this first meeting Dilip and Rolland discussed Indian and Western music. Dilip was doubtful about the possibility of Indian music making inroads into the European hearts and minds because it was fundamentally so different from the European music. While the European music was based on harmony the Indian music had melody as its basis. He wondered whether Europeans would at all like Indian music which was deficient in harmony. Rolland did not agree with Dilip’s views. He was of the opinion that it would be wrong to exaggerate the difference between the two systems. He thought that each system had a unique basis while it sacrificed something else, and even if westerners did not fully comprehend Indian music, they would definitely appreciate it to a certain measure and that should be quite alright. Rolland expressed this at great length in a letter he wrote to Dilip subsequently.

In 1922 Roy left Cambridge – he had given up his Tripos in Mathematics – to tour the Continent. Rolland had organised a lecture for him on Indian music at International League of Women for Peace and Freedom at Lugano. From there Roy went to Zurich, Venice, Vienna and Budapest. At the end of this travel, Dilip once again called on Rolland, in the Swiss village of Villeneuve where the author was then residing. This time a key theme which they discussed was the social obligation of art and artist.

Dilip asked Rolland whether not any artist was living a life of leisure and privilege only on account of the hard labour of countless working class people. He wondered whether this was just and fair. Rolland replied proclaiming that any true artist also underwent a lot of suffering in life without which the creative process of producing great art was just not possible. He was of the firm view that it was the artist’s primary duty to create his art but surely he should devote any spare time to service of the society. He was of the view that art itself serves the society. Rolland gave examples of how theatre or music touched the life of working class people and how the latter were nourished through art which very often was often the only available nourishment in their lives.

Rolland made some striking remarks. He said that “a single symphony of Beethoven is certainly worth half a dozen social reforms.” “Then again”, he continued, “the more downtrodden a community, the greater its spiritual need of art. The more grinding the miseries from without, the more fortifying the consolation from within.” Rolland gave the example of Tsarist Russia that during that period of despotic tyranny their arts and crafts underwent “explosions of splendour.” He saw this as an illustration of the refusal of the Spirit to be tamed by adversity. “The more you try to crush the spirit of a people, the more they turn back to their inner resources of which art is an outflowering,” Rolland declared.

When Dilip asked whether not the artist created for a handful of privileged beings, Rolland rebuffed this by saying that with the advances in technology, an increasing number of working class people got leisure for cultivation of an aesthetic and intellectual life and that woukd only grow in future. He gave examples of increase in the number of free museums, art galleries, public parks, libraries, popular theatres and cheaper concerts. And he thought this was all in the right direction.

Rolland also thought that true pleasure or joy was never ephemeral but had the potential of transforming a human being. “Every true thrill and delight must of necessity elevate us, bequeathing its leaven of permanent inspiration,” was his conviction.

He felt that an artist could achieve best in what he was cut out for and that the creation of truly great art demanded and drew the very best from the artist.

He said, “If Beethoven were suddenly to materialise before me today racked by the problems of human misery, I would only say to him: ‘Brief is our span in life, sire, so make haste to give us what you have to give. Because were you to be carried off today, the harm done to the world would be irreparable – since none else can give us what is upto you to give.'”

In a letter written to dilip in 1922 Rolland emphasised rhe point by saying, “As for yourself, believe me, your artistic gifts impose on you corresponding obligations which are not a whit less imperative than those of charity or service. For a man’s duty is not done if he thinks only of his contemporaries his neighbours : he has to take count of his debt to the Eternal Man who, emerging out of the lowest depths of animality, has climbed obstinately through centuries toward the light. And what constitutes the ransom for the liberation of this Eternal Man in bondage is his conquest of the Spirit. All the efforts of the savant, the thinker and the artist compete for this heroic campaign (campaign in the sense of battling against odds); whoever among them repudiates this obligation – were it even for the sake of altruism – betrays his ultimate mission.” This definitely inspired Dilip to consider music as a fulltime vocation even when that was not something in vogue from ones belonging to his social class.

They also discussed great European minds like the Russian trio of Tolstoy, Dostoiekvsky, and Turgenev. While Rolland considered Turgenev to have been a greater artist than Tolstoy he firmly felt that Tolstoy was a ‘gigantesque force de la Nature’ and his genius was of a higher order than Turgenev. They also discussed great French writers Balzac and Zola, and some ideas of Nietzsche.

The two in their meetings also discussed ideas of progress. Rolland was of the view that progress could not be seen in linear terms and it was very hard to ascertain if mankind was at all progressing. He gave the example of art of prehistoric men which in many instances surpassed that of the present times. Rolland’s position was quite Indian and un-Western in the sense that he did not share the unbridled optimism of many in the West that mankind was on an unquestionably progressive career. But Rolland was of the view that an individual, nevertheless, should have a mission. “Let us act up to our highest lights available and let our aims be the highest we can focus our gaze on,” he told Dilip.

Dilip paid a visit to Rolland once again in 1927 during a western tour where he met with success with the reception of his lecture-demonstration in Edinburgh and Vienna. Rolland had been studying Hindu and Buddhist scriptures for several years. But during this time he was particularly occupied with voluminous literature on Sri Ramakrishna and Vivekananda. Rolland’s interest in them had been kindled by Tagore who had said “if you want to know India read Vivekananda. In him everything is positive nothing negative.” Rolland discussed with Dilip these two great spiritual teachers and wanted to understand and locate them in the historical context of India’s spiritual traditions and indeed the Light they could give to thewhole world. He had a correspondence with the then President of the Ramakrishna Order, Swami Shivananda who delegated the task of providing Rolland with all possible help and information to a young monk Swami Ashokananda who was then the editor of the Order’s english language journal – ‘Prabuddha Bharata.’

In 1929-30 Rolland published the French editions of the biographies of Sri Ramakrishna and Swami Vivekananda (titled ‘Vie de Ramakrishna’ and ‘Vie de Vivekananda’.) This was an important step in propagating across the western world the spiritual ideals that Sri Ramakrishna and Swami Vivekananda stood for.

Rolland based his idea of ‘Oceanic Feeling’ on the spiritual experiences of Sri Ramakrishna and referred to this in a letter he wrote in 1927 to Sigmund Freud. The latter did take note of this and alluded to this in his subsequent works – ‘Future of an Illusion’ (1927) and ‘Civilization and its Discontents’ (1929). However, Freud did not seem to have interpreted it the way Rolland would have probably liked.

While describing Vivekananda, Rolland went into raptures : “His pre-eminent characteristic was his kingliness. He was a born king and nobody ever came near him either in India or America without paying homage to his majesty….It was impossible to imagine him in the second place. Wherever he went he was the first…Everybody recognised in him at sight as the leader, the annointed of God, and the man marked with the stamp of the power to command.”

Rolland described the experience his study of Vivekananda had upon him: “His words are great music, phrases in the style of Beethoven, stirring rhythms like the march of Handel choruses. I cannot touch these sayings of his, scattered as they are through pages of books at thirty years’ distance, without receiving a thrill through my body like an electric shock. And what shocks, what transports must have been produced when in burning words they issued from the lips of the hero!”

Rolland felt certain of the deep impress Ramakrishna-Vivekananda had made on the great Indian trio of Gandhi, Sri Aurobindo, and Tagore. He wrote, “The present leaders of India : the king of thinkers, the king of poets, and the Mahatma – Aurobindo Ghosh, Tagore, and Gandhi – have grown, flowered and borne fruit under the double constellation of the swan and the eagle.”

By the time of his 1927 tour, Dilip’s views on how Europeans would receive Indian music had undergone some change as he himself had discovered that in his exchanges with European audiences. Rolland and his sister again urged their Indian friend to publish his music in Europe. However, finding Roy uncertain again Rolland said :

“Is it for us to grumble and vaccilate lest our work should be ill-received? Why must you always be probing the fitness or unfitness of your audience? Give what you have to give, and with both hands. If there is anything of lasting value in your contribution, believe me, it can never altogether miscarry.”

Rolland was of the view that any work of art appeals to its audience in myriad ways, many times in ways not even thought of by its creator. He gave the example of his work ‘Jean Christophe’ which he said had appealed to thousands of people in as many ways but not a single person, he thought, had grasped the author’s own idea. And he thought it really did not really matter.

The two also discussed whether music aged with time. Rolland thought that it was indeed true with regard to European music. He also thought that the standardised method of notations which follow any piece of European music was the main reason behind it. But he thought that it was indispensable as the “high superstructure in the realm of music, erected on the plinth of harmony, would have been unthinkable without some system of notation.”

He also concurred with Dilip that the reason Indian music continued to retain its freshness was because of continuous improvisation – “the executant in Indian music created at every step, while in European music he was but an interpreter.”

But Rolland was also of the view that the fact that European musicians wrote their music ensured that they remained creative. He explained this to Dilip that “as soon as a piece of music is written down, the creative mind heaves a sigh of relief – of fulfilment as it were. For the very act of writing satisfies the artists’s hunger, the thirst, the imperious need for self-expression through outpouring. And this release gives his mind respite which in its turn makes it avid again for new creations.”

That was Dilipkumar Roy’s last meeting with Romain Rolland. He expressed his debt to him in his memoirs ‘Among the Great’ that no one more than Rolland had given him greater insights into music. They corresponded with each other once in a while till Rolland’s death in 1944.

Rolland later wrote of Roy that he had no ordinary intelligence.” It is indeed remarkable that a young Indian in his twenties had made such an impression on the world renowned Nobel Laureate, who some thought was the greatest living European and conscience-keeper after Tolstoy’s departure from the world stage.

Romain Rolland felt a profound kinship with India. The following words that he wrote in a letter to Dilip resonate with the deep feeling he had for India: “I am persuaded, my friend Roy, that I must have descended the slope of the Himalayas along with those victorious Aryans. I feel their blue blood coursing and throbbing in my veins.”

Rolland’s heart was universal in is sympathies. One of his later books was titled ‘Je ne Veux pas Me Reposer’ (I will not rest). And in a moving letter to Dilip in 1933 he wrote : ” What use is it to me to know that the One on high embraces and rules all the waves of the present? My first duty as a boatman is to save those who are drowning in these waves or else to perish along with them. Vivekananda’s cry of ‘Mon Dieu, les miserables’ (My God, the miserables) is engraved in my flesh.”

That was the great Romain Rolland whose heart was always alert to anything human in any part of the world.