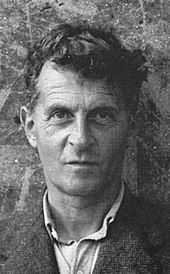

On the Republic Day of 2004, when I was not yet 26, there appeared in Times of India, which was then still a daily of passable reputation, a somewhat abstruse article I wrote – a concoction of convoluted philosophical strands primarily hinging on that tormented genius, Ludwig Wittgenstein – I have appended the article and the web link to it at the end. It so happened that I knew and had some closeness then with a couple of intellectuals steeped in western philosophy and social theory who discussed names like Derrida, Foucault and Wittgenstein like some others of my acquaintance did of soft drink brands (and some not so soft ones.) Under their influence I heard of Wittgenstein and found a copy of the his famous work the Tractatus Logico Philosophicus (the only published text in his whole life) with the English translation bearing this famous Latin title. I, of course, could not comprehend anything after a few statements (it was written in form of a mathematical theorem with serialised statements acting as propositions.) But these well-read senior friends of mine gave me a gist of what they thought Wittgenstein was trying to say in that highly celebrated but scarcely understood work which changed the course of Philosophy for ever. Wittgenstein himself expected few to understand the work and subsequently disavowed it himself saying there was much wrong in that.

Ludwig Wittgenstein, much like his namesake Ludwig Van Beethoven, had always been a troubled and tormented soul. Born to a steel tycoon, one of the wealthiest men in Europe, and one who was markedly imperious and overbearing in his ways as a father, Ludwig was taught at home, hardly mixing with any children of his age, and not sent to any school till teenage. Three of his four brothers committed suicide and the foreboding that he too was to eventually meet his end by his own hand someday remained his constant companion – indeed in his later years at Cambridge he often told his students or colleagues that he was going to kill himself later that day. If Shakespeare thought Hamlet lived on the border of insanity it was because he had never known Wittgenstein.

When finally admitted in a school Ludwig had as one of his contemporaries a boy who hardly distinguished himself in anyway then but later would be the author of Mein Kampf. It is often conjectured upon that whether the two had any close association then but it has never been established.

Ludwig studied mechanical engineeing in Berlin and aeronautics in Manchester but constantly agonised by deep philosophical questions he one day presented himself unannounced in the chamber of Bertrand Russell at Trinity College in Cambridge, the only philosopher of the day who made sense to Wittgenstein. Russell had heralded a completely novel approach to philosophy endeavouring to place it on sound foundations of logic, as he had earlier done to Mathematics through his 1903 work Principia Mathematica. Wittgenstein had been dissatisfied with the earlier speculative approach to philosophy and found them shallow or dishonest or both. He thought little of the German greats of the eighteenth and nineteenth century. Russell asked him to write on any topic related to philosophy in order to answer Wittgenstein’s question whether the latter was an idiot or not. The idea was to ascertain whether he should do aeronatics or philosophy – if he was gauged to be an idiot he would continue doing aeronautical engineering else take up philosophy. When Ludwig gave a few pages of his writing Russell told him that on no account he should pursue engineering and definitely take up philosophy. Wittgenstein abandoned engineering for good and began attending Russell’s lectures at Cambridge.

Wittgenstein often disturbed his teacher during his lectures objecting to and pointing fallacies in ideas which Russell and everone else in the class thought were based on soundest common sense. Russell was naturally exasperated at such moments, which were hardly scarce, but on later reflection found that this eccentric pupil was often right and he wrong. Russell himself, it is said, became shaky in pursuing fundamental philosophical work after that. In his autobiography he mentioned his time with Wittgenstein as one of the greatest intellectual adventures he had in his life. He thought that Wittgenstein was the closest that came to the idea Russell had in his mind of a ‘genius.’ The pupil came to have a lasting influence on the teacher.

Wittgenatein had a close friend in David Hume Pincent and the two for a while lived in a cabin in an isolated place in Norway where they seemed to have a joyful time, their time divided between with idyllic boat rides and most strenuously cerebral work. Pincent’s death at the age of 27 affected Wittgenstein profoundly as the former was perhaps the only friend he ever had. While Wittgenstein never married he had once attempted to plight his troth to a lady about whom not much is not known but his proposal was promptly turned down.

In 1913 when his father passed away, the inheritance Wittgenstein received made him one of the wealthiest men on the continent. But the ascetic passed the entire fortune to his sisters and also donated anonymously to struggling artists and writers.

When the First War broke out Wittgenstein enrolled himself in the Austrian forces, was involved in some highly perilous moments, and was held in captivity for a couple of years in Italy. He received several decorations later for his services. This phase of war when there were shots and bombshells all around him was it seems something he badly needed as it enabled him to see death eye to eye. He himself remarked that the war saved him life and that “I dont know what I would have done without it.” One reckons that bereft of this experience Wittgenstein too might have followed his brothers and ended his life.

He also seemed to have developed a deeper mystical and spiritual dimension during the War. Once moving with the troops in southern Poland, he purchased a book – Tolstoy’s ‘Gospel in Brief’ – which he always kept with him. While most regard Wittgenstein as an agnostic, some of the jottings in his notebook during the War years reveal a decidedly mystical temperament, for example his conviction that conscience represented the voice of God.

It was during these days of war and imprisonment that Wittgenstein completed the work he started in Norway aimed at nothing short of answering all questions of philosophy once and for all. This was the Logisch Philosophisch Abhandlung written in German (the English translation published as Tractatus Logico Philosophicus) with which he thought he had finished and destroyed philosophy for ever as nothing more was left to be said.

The Tractatus was published in 1921 and Bertrand Russell upon studying it commented that it was either all right or all wrong but it would take him many years to decide that. The concluding lines of the Tractatus are some of the most profound ever uttered like when Wittgenstein stated the limits of language and the futily of settling deeper philosophical questions by way of words – ‘Whereof one cannot speak thereof one must be silent’ or ‘Death is not event of life. One does not experience it.’

Being convinced that there was nothing more to be done in philosophy, he retired to take up the job of a gardener in a monastery and then the role of an elementary school teacher in a village. That Wittgenstein had a personality far from normal was all too clear during his days as a schoolmaster. While doing arithmetic he refused to give any sums to children that had problems pertaining to money (and arithmetic was thought to be mostly about skilling children with money calculations.) While the children were happy with him when he took them outdoors he often physically punished them in states of fury when they failed to answer what he thought was pretty elementary. It was not infrequent that the parent community was annoyed with this highly eccentric teacher, the like of whom they had never known. Once a pupil was punished rather severely and with the unhappy prospect of a legal action glaring at him, Wittgenstein fled from the area. This ended his misadventure as a school teacher.

He spent the next year designing a house for his sister where he employed the knowledge of his training in engineering and had plenty of design and architectural sophistications. When that ended the call philosophy of beckoned him once again and he went back to Cambridge asking Russell and his colleague G.E. Moore for a Fellowship or Professorship at the University. While they certainly wished to be of help they politely (one fancies with some trepidation) tried to explain that he did not have the necesary qualifications and advised him to enrol for a doctorate. Wittgenstein thought that the Tractatus was as good a doctoral thesis that could ever be. Because of their stature at the University the two Professors arranged the formalities and to their dismay were assigned by the University the task of taking the thesis defence of this maverick candidate. The defence, one imagines, was a farce, with Wittgenstein at the end of it, patting the backs of the two Professors saying that he knew that they would not understand a word of his thesis. With their agony ended the two stalwarts who bestrode the world of academic philosophy like colossal figures did the only thing they thought sensible under the circumstances – Wittgenstein was now Dr Wittgenstein and a Professor at Cambridge.

During these years he took time to work as a hospital porter during the Second War carrying medicines to the patients. He also worked as a laboratory assistant for a while at a paltry wage. Along with a friend he had once seriously mooted moving to Soviet Union and work as a manual labour but apparently the Soviet authorities told them they were welcome to work as high end academicians and not in an ordinary working class role as there was no dearth of takers for that. The idea was thus duly aborted.

In his classes at Cambridge Wittgenstein displayed a state of high nervous anxiety often strung to the point of a break down. He often cursed himself in his class and withdrew into silence for long periods when his pupils also became anxious of what was to come. He often shouted and said things like ‘damn my bloody soul.’ He told that his class would be of any use only to those who suffered mental cramps and his role was only that of a masseur helping relieve them of those cramps.

Interestingly in the evenings he often went to the cinema and seated himself in the front row so that he could not see anything but the screen and not have anything else to distract, least of all his own punishing thoughts.

It seems that more than any interest or absorption in cinema thewe were exercises to ward off tormenting questions which like Banquo’s ghost never ceased to take possession of his mind. He occassionally read detective fiction and that was a rare relaxation in his life. He was greatly fond of Dostoevsky’s ‘Brothers Karamazov’, a novel dealing with themes like faith, atheism and free will, and a work said to have been a favourite of men like Albert Einstein, Sigmund Freud, James Joyce, and Franz Kafka. He also had some interest in western classical music and regarded Mozart and Beethoven as ‘Sons of God.’

Wittgenstein regarded Philosophy as ‘a struggle against the bewitchment of our intelligence by language.’ And he was clear about the goal of philosophy – to show a fly a way out of the fly-bottle.

He often thought that his life was spent in a futile way. He had movingly remarked that “I ought to have done something positive with my life. To have become a star in the sky. Instead I remained stuck on earth and now am gradually fading out.”

Wittgenstein developed prostrate cancer and was relieved that life would end soon for him. He actually became sad when he told that there were drugs which could keep him going on several years. As he did not want to die in a hospital he spent his final days with the family of his doctor at Cambridge. His final words were “Tell them I had a wonderful life.’

Wittgenstein died at the age of sixty-two but always looked a good fifteen years younger till his last days. He left a great number of unpublished manuscripts that were later published by his peers and pupils as ‘Philosophical Investigations’ that was often hailed as his greatest achievement though Bertrand Russell thought that early Wittgenstein of the Tractatus was greater. However, the larger opinion strongly favours the ‘Philosophical Investigations’ and many consider it to be the greatest work in Philosophy in the twentieth century.’

I cannot flatter myself that Ludwig Wittgenstein has had any particular impress on me but as I recollect days from a distance of two decades I remember that the fact that Wittgenstein had dropped everything to become a school teacher did have some resonance with me way back in 2003 as I too was dropping out of a mainstream career and setting up a Children’s Home in a rented building.

I cannot gainsay that whenever I think of this most extraordinary person it is difficult to remain unmoved. While I cannot comment anything about Wittgenstein’s philosophy I know for sure that he was wrong on one account – he was certainly a star and has never faded with time, indeed has been more luminous after he has moved on from our midst.

II

I am appending below my article published on the Republic Day of 2004. I had almost forgotten it and when I revisited it recently it was appeared to me that it was a different person who wrote that.

The World is what we think it is

By Vinayak Lohani, 26th January 2004.

Since ages we have been witness to incessant face-off between faith and logic. European enlightenment exposed certain flaws in blind faith and ushered in an era of rationality, and logic became the dominant paradigm. Metaphysics walks a tightrope between rationality and faith and it is here that the dissension between the two is sometimes at its peak. Oriental metaphysical thought like the Advaita Vedanta are expounded on as rational a ground as metaphysics could ever be. But at a certain point they have to forsake logic due to its inherent limitations and enter a realm where tools of logic are no longer applicable and things have to be taken on faith.

To understand these limitations, we have to first understand the nature and mechanism of logic. Logic is a continuous build-up, a rearrangement of certain propositions which are known as elementary or object-propositions.These propositions, which we call ”facts”, are based on direct perceptual know-ledge or empiricism.These elementary building blocks of the logical process hinge upon the validity of human perception and are limited by the latter”s scope and validity. That”s why theories such as the geocentric theory or even Newtonian mechanics that were once accepted as empirical truths, were later discarded when such perceptions were invali-dated in light of newer revelations of modern science.

Amongst western logicians it was Ludwig Wittgenstein, the Austrian philosopher who came nearest to proving the futility of all logical speculations to attain the Supreme Truth. In his seminal work Tractatus Logicus Philosophicus Wittgenstein argued that logic is always conveyed through the instrument of language which itself is based upon direct human perception. Language by its very definition is based upon the collective consciousness of all human beings, and is not drawn from perceptions particular to an individual. So it can deal with and arrange relationally only those propositions that are commonly and nearly identically perceived through human senses. Moreover, he argued that since the method of logic starts with elementary propositions as the premises and works upon its rearrangement, all it ends up with is another proposition dependent entirely upon the earlier ones, and thus is a result of a tautology. It reveals everything already known; so it reveals nothing new.

Wittgenstein analogises the logical process with mathematical equations and says that starting from certain equations when we transform an equation, or generate new equations, we are actually doing nothing but playing with the same identity. The same applies to any other logical process dealing with forms.

Vedanta and Wittgenstein upheld that even the elementary propositions that purportedly act as absolute premises, are not actually absolute. So if we start wrong we would always be wrong. Any method dependent upon the senses is inadequate in capturing the Absolute.We can never speculate upon what is beyond our senses.The human thought process is logical in nature as it uses words as the building propositions. What we sense could be known and expressed; but not what we do not. Every individual has to himself experience this extra-sensual Absolute premise that we call God. The universe, which is the macrocosm, is just a chimerical reflection of the microcosm that is our ”I”, and is therefore limited by it.The Absolute cannot be achieved through either thought or language. Wittgenstein, who announces that one”s conception of the world by logical necessity has to be limited by one”s thought and language, is only confirming that the world is not what it is, but what we think it is.