The year 1893 was a remarkable one in Indian history. Two unknown Indians went to the West that year, returning to be among the greatest figures of their times – Swami Vivekananda and Mahatma Gandhi. Much less remembered, is the journey of another young Indian, who undertook the journey in the opposite direction. Aravinda A Ghose, for that is how Sri Aurobindo wrote his name then, sailed from England to India. He was not even 21 and had lived in England for 14 years. Now Baroda would be his base in India for the next 13 years. This period was a very remarkable phase in his extraordinary life.

A little background may be necessary here. Dr Krishna Dhan Ghose, a surgeon working in Bengal, wanted his sons to be brought up as Englishmen. He packed them off to England in 1879. Aurobindo, his third son, to whom he had given the middle name of Ackroyd, was then seven. ‘Ackroyd’ was the family name of Annette Ackroyd, a dear friend of Dr Ghose. She was a remarkable woman, one of the early pioneers in girls’ education, who founded the Hindu BalikaVidyalaya in Calcutta (later merged into Bethune School), and had translated the Baburnama and Humayun-nama from Persian into English.

The three brothers – Aurobindo and his elder brothers, Benoybhushan and Manmohan – were left to the care of one English couple, Mr and Mrs Drewett, in Manchester. After some home-tutoring Aurobindo attended the Manchester Grammar School. But after five years, the Drewett couple relocated to Australia and it was Mr Drewett’s elderly mother who became the guardian of the Ghose brothers. They moved to London and got enrolled at the St Paul’s School as day scholars.

Aurobindo was a brilliant student, having a particularly astonishing capacity for learning and mastering languages. Even while at school, he studied the classical literature of Europe in Greek and Latin, as well as modern European languages like French and Italian. He read classical masters like Cicero and Virgil, Homer and Plato. He also wrote verse in the new languages he learnt. Sports and games, an inseparable part of leading English schools, did not quite interest him.

After his High School, he won the Senior Classical Scholarship to read Greek and Latin at King’s College, Cambridge. By this time, the brothers were hardly receiving any financial help from their father, and lived almost in penury. It was to fulfil his father’s ardent wish, and perhaps also to receive the healthy probationary stipend, that he appeared for the prestigious Indian Civil Services (ICS) and succeeded in the first attempt, at the age of 18. He had secured record marks in Greek and Latin. A two-year stint in the University was a stipulated part of the ICS probationary period and during this Aurobindo also studied Political Economy, Law and Jurisprudence. He also took basic courses in Sanskrit and Bengali. However, despite receiving multiple calls, he did not appear for the mandatory horse-riding test, and got disqualified. It was an extraordinary occurrence with hardly any precedent.

For some years before this, a strong feeling was raging in his young mind to return to India and serve the country of his birth and ancestors. His father too, by that time, felt the great misery of his countrymen under British rule, and the sentiment was being strongly reflected in his letters to his sons. At Cambridge, Aurobindo was associated with the Indian Majlis that enabled him to get greater familiarity with the current political debates concerning India. He was also interested in the Irish struggle and admired Charles Parnell to the extent of writing a poem when the Irish leader died. After the end of his second year at Cambridge, Aurobindo became clear that his future lay in India.

Road To India Through Baroda

It was at this juncture that Aurobindo happened to meet Maharaja Sayajirao Gaekwad III, the ruler of the princely state of Baroda, who was on a visit to England. The Maharaja, then 30, had already built a reputation of being a very progressive ‘native state’ ruler, a reputation perhaps only matched by the Wodeyar of Mysore. The Gaekwad had been adopted at the age of 12 from an extended branch of the family and made the ruler. When he came of age, he followed policies like increased access to primary education, prohibition of child marriage, promotion of trade and industry, bringing the railways to the region, and other general welfare measures. These measures led to considerable social and economic development in his state.

He founded, among other things, the prestigious Baroda College, which later became the Maharaja Sayajirao (M S) University. He would also later establish the Bank of Baroda. The Maharaja also ran scholarship schemes to support talented Indians wishing to study in leading Western universities – it was on one such scholarship that the young B R Ambedkar would go to study at America’s Columbia University. The Maharaja also had a very competent cadre of officials and experts in various departments of his government and important State establishments, which included many Europeans.

The Maharaja visited England every year on business and used the opportunity to scout for suitable candidates for his State service. His meeting with Aurobindo was arranged by some common friends. Impressed with the 20-year-old youngster, who had chucked the most coveted service in the British Empire, the Maharaja readily offered the opportunity to serve in the Baroda administration. Serving under a benevolent ruler with progressive vision was to Aurobindo any day better than serving the colonial establishment. And within a few weeks of the meeting, Aurobindo was on ship to Bombay. Little did he know that tragic news awaited him upon arrival! His father had passed away. It is believed that his father had been misinformed by someone that the ship carrying his son had sunk, with all passengers losing their lives. Indeed another ship around that time had sunk off Portuguese shores. Dr Ghose could not bear this news and passed away following a cardiac arrest.

As soon as he stepped on Indian land at Apollo Bunder, Aurobindo had a deep, transfiguring experience. He felt relieved of a feeling of darkness that he had experienced throughout his years in England. From Bombay,Aurobindo went straight to Baroda and began to settle in the new conditions. It was not until early next year that he went to see his family, who lived in the pilgrim town of Deoghar (now in Jharkhand, then in Bengal) under the care of his maternal grandfather, Rajnarain Bose. Rajnarain Bose, was a prominent figure of that time, and popularly called a ‘rishi’. He is widely regarded as one of the pioneering nationalist figures in Bengal. As early as 1861 he had conceptualised a ‘society for promotion of nationalist feeling’ and published a prospectus on the same, striking heavy blows on the Anglicised way of living and thinking among the educated classes in Bengal.

Rajnarain was a close collaborator of Nabagopal Mitra and was involved in organising the Hindu Mela, aimed at galvanising the masses with patriotic fervour. Aurobindo’s mother, who suffered from chronic illness for many years, and whom he had not seen for 14 years, lived in Deoghar with her daughter Sarojini and fourth and youngest son Barindra. Aurobindo made visits to Bengal every year, usually during the Durga Puja vacations. Visits to Bengal helped him brush up his Bengali which he had almost never used till then. They also enabled him to come in touch with the Bengali mind of the day.

In due course, Auobindo’s brothers too had returned to India. Benoybhushan, the eldest, was posted in the service of Cooch Behar State, and Manmohan, who had studied English literature at Oxford, returned to hold academic positions at Dacca University and later at Presidency College, Calcutta. Manmohan was also a talented poet and published his works in English. He had many friends in the literary circles of England and personally knew Oscar Wilde.

Aurobindo began to work in the Survey and Settlement Department and later moved to the Dewan’s office – the State Secretariat. The Maharaja also asked him to write his speeches, important memoranda and reports. The Maharaja was well aware of the exceptionally talented person he had in his ranks. Once, upon going through a speech written by Aurobindo, the Maharaja became a bit edgy, and asked him to tone it down. Aurobindo smilingly replied, ‘Your Highness, if I give you a toned down version, do you think the people will take it as being written by you? Then why change it for nothing. The thoughts are yours and that is what is important.’

The Maharaja had a lot of affection for Aurobindo, and very often asked him for breakfast at the Laxmi Vilas Palace. He surely valued the rich intellectual companionship he received. Aurobindo was often invited to many performances of music and dance at the palace. The Maharaja had many accomplished artists under his patronage – he was one of major patrons of Raja Ravi Varma (many of whose masterpieces embellish the Palace walls) and later had masters like Ustad Faiyaz Khan and Ustad Abdul Karim Khan, two of the greatest vocalists of the 20th century, adorn the Baroda Court.

Scholarship And Creative Pursuits

The first half of Aurobindo’s stay in Baroda can be called a phase of splendid isolation. Barring the relationship with family and close relatives which he maintained through his periodic visits, there were hardly any wider social engagements as far as Bengal is concerned. In Baroda, Aurobindo hardly had any company of Bengalis. He had Maharashtrians and Gujaratis as his friends. Among his closest friends were the Jadav brothers – Khaserao and Madhavrao. Khaserao was in Baroda’s legal service while Madhavrao served in the army. There was a young intellectual writer called Phadke. Also a close friend was a Gujarati barrister named Majumdar. He had a close bond with K G Deshpande, his friend from Cambridge, who edited the weekly bilingual journal ‘Indu Prakash’. Through these circles he later came in touch with political currents in Western India and stalwarts like Bal GangadharTilak.

In the initial years in Baroda he lived a largely private life. But for a person like him who could lose himself in books for hours together this was no particular disadvantage. His lack of social life left him with ample time for his creative and scholarly pursuits. Starting with a house near the bazaar, he lived in at least four different houses over the years. They were all modest accommodations, shorn of any luxury. He had more almirahs for books than any other furniture. The shelves were full of masterpieces of literature and philosophy from across millennia of human civilisation. Gems from literature in Sanskrit, English, Greek, Latin, French, Italian, German and Russian were stacked there. He had a collection of 16 volumes of Arabian Nights which he had won as a prize in England. He used to order books from Bombay-based dealers like the Thacker, Spink & Co, where he ran a deposit account. His books arrived in big boxes every month, sometimes even more frequently. He used to study well past midnight. Perhaps his only indulgence during those days was his fondness for the cigar, which he smoked while gathering his thoughts during reading or writing.

He began to learn Sanskrit unaided and soon gained an astonishing extent of mastery. It will not be wrong to say that Aurobindo’s discovery of the Indian soul first happened through its classical literature in Sanskrit. He studied the masters of classical poetry and drama – Valmiki, Vyasa, Kalidasa, Bhavabhuti. He considered Ramayana to be the greatest epic in world literature and Valmiki a greater epic-poet than Homer or Dante. In later Sanskrit literature, he was particularly captivated by works of Kalidasa. He did a verse translation of Vikramorvasi (as The Hero and the Nymph) and partially translated Malavikagnimitram (as Malavica and the King). He translated the Meghdoot in terzarima, and considered his effort very satisfying. Unfortunately, this was lost, along with many of his writings of this period, during the turbulent days of his political activism. He hailed Meghdoot as ‘the most marvellously perfect descriptive and elegiac poem in the world’s literature’. Though he had studied ancient masters like Plato and Epictetus, he did not seem to have great interest in studying modern Western philosophy. As he became more absorbed in profound spiritual questions he undertook a systematic study of Upanishads with the commentaries from masters like Sankara.

During this period Aurobindo also translated sections of the Mahabharata. He later showed this to Romesh Chunder Dutt, who after his retirement from the ICS and subsequent teaching stint in England, was visiting Baroda, and was to later take up the post of the Dewan. Dutt, a formidable scholar himself, had brought out one of the earliest translations of the Ramayana and Mahabharata into English, along with writing the path-breaking treatise of Indian economic history under British rule. He praised Aurobindo’s translation profusely and thought it was clearly superior to his own effort. Around the same time, Aurobindo also translated Bhartrhari’s Neeti Shataka (as Century of Life).

In parallel, Aurobindo also took up the study of Bengali. He began to study Bengali literature from its roots. He studied and translated into English the poetic works of Bidyapati, the great poet in Maithili who was a key influence on early Bengali literature. He also studied and translated works of Chandidas, Jnanadas, Haru Thakur, and Nidhu Babu. In modern Bengali literature, Aurobindo made a careful study of Michael Madhusudan Dutt and was dazzled by his genius. However, the author who influenced him the most was Bankimchandra Chatterjee, the doyen among the Bengali writers of his day. Aurobindo considered Bankim as the prophet of Indian nationalism. After Bankim’s death in 1894, he wrote seven articles on Bankim and his thought in Indu Prakash. In these columns he hailed Bankim as the most towering Indian of that period who gave the country the ‘religion of patriotism’.

All this while, Aurobindo continued with his own poetic pursuits. He usually began his day writing poetry. In 1895, he published Songs to Myrtilla that had many poems written during his England days. He also wrote his Love and Death, based on the Mahabharata legend of Ruru and Pramadvara, but it was not published until he was in Pondicherry. He also wrote a lot of poetry which he never published. During the fag end of his stay in Baroda he wrote several plays like the comedy The Viziers of Bassora based on a tale from Arabian Nights, Rodogune, a play in verse that was a reworking of a French play, and Perseus the Deliverer adapted from Greek legend.

It is interesting to note that a considerable part of Sri Aurobindo’s writing of this period are his translations of works from other languages into English. He clearly enjoyed that as a creative exercise. In addition to the verse-to-verse translations, he also engaged his creative powers in transcreations of prose to verse (like Kalidasa’s Vikramorvasi) and verse to prose (like verses from the Gita).

Aurobindo also picked up Gujarati and Marathi through his friends in Baroda and knew Hindustani well. He got much less occasion to practice speaking in Bengali, a weakness he sorely felt. In order to overcome this, he called for a Bengali tutor who would live with him in Baroda. In 1898, a gentleman called Dinendra Roy began to live with him. Roy has left interesting memoirs of his two years with Aurobindo in his Bengali work ‘Aurobindo Prasanga’.

As A Teacher At Baroda College

It was after nearly four years of routine administrative work that Aurobindo got to do something which he found more to his liking. He was asked to teach French at Baroda College. After a year he was also given Professorship of English. But he was never completely free from administrative tasks and special assignments entrusted to him by the Maharaja. Aurobindo remained active at the College till the end of his stay in Baroda. In due course he was made the Vice-Principal of the College and later functioned as the Acting Principal for a year.

From accounts left by his students, one gets to know that Aurobindo had an overawing presence as a teacher. His classes were not of interactive nature. He usually started the class by reading relevant passages from the sourcebooks, and after that with half-closed eyes, delivered his lecture without any reference notes. He did not ask any questions. On the whole, his delivery did not exactly adhere to academic conventionalities of the subject. He expressed his own thoughts on the subject and his delivery was not necessarily directed towards achieving success in examinations. He also presided over debates and literary events conducted by the students in the College and spoke at the Central Hall of the College. The language in his lectures and dictations was the finest example of classical English and inspired students to strive for higher levels of adeptness in expression. He laid a lot of stress on articulate expression in compositions, particularly underscoring the importance of logical flow of ideas. He always equated clear composition with clear thinking.

Among his students was K M Munshi, who in later life became an eminent litterateur, lawyer, freedom fighter, founder of the Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, and later in independent India, the Governor of Uttar Pradesh. Munshi recounted his interaction with him. While discussing how to intensify the spirit of nationalism the Professor pointed out to Munshi the map of the country and said, “Look at that map. Learn to find in it the portrait of Bharatmata. The cities, mountains, rivers and forests are the materials which go to make up Her body. The people inhabiting the country are the cells which go to make up Her living tissues. Our literature is Her memory and speech. The spirit of Her culture is Her soul. The happiness and freedom of Her children is Her salvation. Behold Bharat as a living Mother, meditate upon Her and worship Her in the nine-fold way of Bhakti.” Munshi also mentioned that when asked about what books one should read, the Professor suggested Vivekananda, whose works had just come out in the previous few years.

Marriage

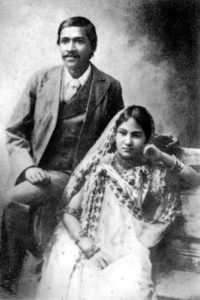

An important event in Aurobindo’s life was his marriage to Mrinalini in 1901. He was then 29. Interestingly, it was he who had placed a matrimonial advertisement in Calcutta newspapers. Mrinalini, who was 14 then, hailed from a prominent aristocratic family based in Shillong. She had received school education, something certainly not common in those days. However, barring a few occasions (sometimes in Deoghar or Baroda, and on some occasions at Mrinalini’s parents’ place) they lived separately.

Mrinalini usually lived with her family in Shillong and later in Calcutta. Even during Aurobindo’s visits to the East, claims on his time were too much to allow him spend much time with his young wife. He, however, did keep in touch through correspondence. The letters to Mrinalini are valuable in revealing what went on in Auobindo’s mind during those years. While he was always known to keep his innermost thoughts to himself, in many of these letters one sees a soulfully candid outpour of feelings. He tried to share the myriad pulls his mind experienced which he described as mania. He tried to impress upon her the idea that his life was meant to be a sacrificial offering to the country, and that a common man’s joys and aspirations were never to be his. He also shared the feeling that he was a chosen instrument of God to redeem the country from its present fallen condition. He confided to her that he was not even the master of his will but only an instrument in the hands of God.

He exhorted his wife to live a God-centred life, expressing hope that it would accelerate his own spiritual progress. Mrinalini lived a life reconciled to the circumstances, and in 1918, many years after Aurobindo had retired to Pondicherry, she passed away, succumbing to the Spanish flu. But she did get a great blessing in the form of Diksha (discipleship) from Holy Mother Sarada Devi, the wife and spiritual consort of Sri Ramakrishna to whom she was taken by Sudhira Bose, who managed the girls’ school started by Sister Nivedita.

Evolution Of His Politics

Visits to Bengal, without doubt, supplied the necessary leaven needed to quicken Aurobindo’s political consciousness. Calcutta was not just the capital of British India but also its intellectual and political epicentre. As early as 1893, he had started to write a series under the title ‘New Lamps for Old’ in Indu Prakash, which were the earliest vocal expression of his political views. While the Indu Prakash largely maintained a Moderate line, his unsigned articles, in which he strongly criticised the Indian National Congress, drew a lot of attention. He pointed out that the Congress was hardly representative of Indian society, and did not deserve to be called a ‘National’ organisation. The elite nature of the Congress did not inspire much hope in him. The toiling classes of India, he thought, were the key to any impactful national movement.

He wrote that while the Indian proletariat was ‘torpid and immobile, he is a very great potential force and whoever succeeds in understanding and eliciting his strength, becomes by the very fact master of the future’. He called the Indian masses a volcano which might erupt one day. Clearly Aurobindo in these writings was anticipating Gandhi and his later mass-based transformation of the Congress. Fearing a backlash from the authorities against the paper, Maharashtrian stalwart M G Ranade, who himself in the past had edited Indu Prakash, advised him to exercise restraint. After a year or so, Aurobindo lost interest in writing for Indu Prakash and continued his studies and literary activity.

However, through the years, his mind was brimming with political ideas of a completely different kind. He thought that one way to free the country of the British yoke was through armed uprising. He knew it would be a very long-term plan, yielding fruit perhaps after decades. But he was thinking of finding ways to sow its seeds. The assassination of the British civil servant W C Rand by the Chapekar brothers in Poona in 1897 had raised the mood of armed revolutionary action against the British. Aurobindo was in contact with a Maharashtra-based group who were hatching a plan to bring about a revolt in the British Indian army. It is said that Aurobindo travelled to central India (possibly the major military cantonment of Mhow near Indore) to have a secret dialogue with the Indian regiments regarding this but nothing certain is known about this.

Aurobindo’s plans got a significant push in 1899, when a strongly built Bengali Jatindranath Banerjee (not to be confused with Jatindranath Mukherjee or Bagha Jatin, the iconic revolutionary leader) visited Baroda in garb of a wandering monk. He met Aurobindo and told him of his ardent ambition of becoming a soldier, a chance he could not get in the British Indian Army, as those were the days when no Bengalis were recruited there. Through his good offices, Aurobindo helped him get inducted in the Baroda State Army. After Jatindranath (Jatin) had finished his year-long training, Aurobindo despatched him to Bengal to build and organise revolutionary societies in that province.

In 1901, Aurobindo’s youngest brother Barindra, eight years his junior, visited him in Baroda. Barindra, born in England, had moved back with his parents and had been educated in India. Because of father’s premature death, straitened circumstances, and mother’s condition, he could not achieve the same academic merit as his elder brothers. He tried his hand at ventures like running a stationery and tea shop in Patna but soon ran out of money as well as interest. However, he was of enterprising and adventurous nature, almost bordering on daredevilry – a characteristic he would retain all his life. Barindra almost worshipped Aurobindo, who, perhaps, was more patient and sympathetic to the former’s unusual ways than others in the family. Barindra left himself freely in Aurobindo’s hands to be moulded as the Master liked.

Barindra too had a natural attraction for heroic action associated with revolutionary methods. As a part of his political education, Aurobindo made him read works ranging from Edmund Burke’s study of the French Revolution to M G Ranade’shistory of the Marathas. Through his friends in the Baroda army, Aurobindo also arranged for Barindra’s basic training in handling arms and receiving a general exposure in military aspects. In 1902 Aurobindo sent Barindra to Calcutta to help Jatin and develop the revolutionary movement there.

Remote Coordination From Baroda

Inspired primarily by Bankim and Vivekananda’s ideas to develop strong bodies and strong minds dedicated to the nation, a sort of movement took off of physical training and discipline. Many of them had the covert goal of revolutionary action against the foreign rule. There were a number of such small groups and loose networks operating not just in Calcutta and its suburbs, but also in far-flung towns and villages of Bengal. The most important of them was the Anushilan Samiti. The Samiti was founded by a Calcutta-based barrister, Pramatha Mitra, and had as its mentors persons like Sister Nivedita and Surendranath Tagore (Rabindranath’s nephew).

It operated in the garb of a gymnasium society, drawing its name from Bankim’s work AnushilanTattva. Jatin, Aurobindo’s pointman in Bengal, teamed up with Barrister Mitra and helped the network grow far and wide. During his visits to Bengal, Aurobindo too visited villages in the districts to see the expansion of the work. Barindra worked with Jatin for some time but the two had some differences and as a result Barindra returned to Baroda.

In 1902, Sister Nivedita visited Baroda to meet the Maharaja and enlist his support for the country’s national movement. After the passing away of her Master – Swami Vivekananda – in July 1902, she had been travelling the length and breadth of the country, striving to build a national consciousness among the Indian people. She was trying to awaken the national soul in different fields of national life like education, arts, sciences, and was exhorting people – both eminent as well as common – to serve the country. She was a prolific writer. Aurobindo was familiar with her literary works, and was deeply impressed by her book – Kali, the Mother. He went to the railway station to receive Nivedita and had her settled at the guest house.

Nivedita urged Aurobindo to play a more direct role in the National Movement, and also advised him to relocate to Calcutta – for that is where she thought he could do most. Aurobindo was most favourably impressed by the Sister’s personality. The two kept in touch during Aurobindo’s future visits to Bengal, and had a closer association during the latter’s subsequent relocation to Calcutta in 1906 when he used to visited her at her Baghbazar quarters. Later still, when he finally left Calcutta for Chandernagore and then for Pondicherry, it was to Nivedita that he entrusted his journal Karmayogin.

Later in his life Aurobindo recalled: “She was a true revolutionary leader and talked freely of revolutionary ideas. There was no concealment about her. It was her very soul that spoke. Whenever she met she spoke about politics and revolution. But her eyes showed a power of concentration and a capacity to go into trance. She was fire, if you like. She did India great service.” When Aurobindo visited Calcutta to assess the progress of the work, he organised a coordination committee for the Anushilan Samiti with members like Sister Nivedita, Barrister Mitra, Surendranath Tagore, and SaralaGhoshal (later Sarala Devi Choudharni, Rabindranath’s niece and editor of the journal Bharati, who too, a few years back, had been energised by Vivekananda towards greater action for the cause of the country).

These were the years when Aurobindo also followed the proceedings of the Indian National Congress. He attended the Congress session for the first time in 1902 in Ahmedabad and did that a few more times. He was naturally drawn towards the politics of Tilak, who was by then beginning to dominate the national scene. Tilak too found in Aurobindo a kindred spirit. Aurobindo met Tilak many times, and had engaging discussions with him. He along with Tilak, arranged for Madhavrao Jadav’s military training in Germany and bore the costs.

Around 1905, Aurobindo drew an elaborate plan to make a temple dedicated to the Mother-Nation. How this came about is something interesting as well as bizarre. Aurobindo, Barindra, and their friends sometimes engaged in automatic writing and séances. Aurobindo viewed them as experiments; he held that it revealed more about the subconscious stratum of the person acting as the medium than anything else. In one such séance session, Barindra, acting as a medium to the spirit of Sri Ramakrishna, wrote the latter’s message as ‘Mandir Gado’ (build the temple). Feverishly excited, Barindra urged Aurobindo to take this as a divinely ordained instruction. The idea possessed them for a long time and Aurobindo first put his thoughts down in a masterly pamphlet he published called Bhawani Mandir. It was a prospectus for building an order of selfless workers dedicated to the service of the country, taking the power and blessings of the Divine Mother, Bhawani.

Clearly, the imprint of Bankim’s ideas was strongly present in Aurobindo’s conceptualisation of this project. He imagined the Bhawani Mandir as a training ground, a sort of monastery for selfless and dedicated national workers, who would work to make the country regain her supreme glory. The two brothers often went to scout for a suitable place for building this temple in the jungles in the Vindhya ranges. Aurobindo and Barindra had also chosen a place about 50 km from Baroda, called Chandod on the banks of the Narmada. Being the confluence of three rivers a special dimension of holiness was associated with it. Though the project did not see the light of day, the pamphlet itself was a source of inspiration to countless revolutionaries of the period.

The year 1905 was a tumultuous one in the history of India when the partition of Bengal was announced. It also had the unintended outcome of galvanising the country, particularly Bengal, into patriotic fervour and action as few events before that had. Aurobindo now knew for certain that it was time for him to move to Calcutta. In February 1906 he took leave to travel to Calcutta and spent around three months there. He came back for a brief period and left after taking an indefinite leave of absence. This was the end of his days of service with the Baroda State.

He had accepted the post of Principal at Bengal National College in Calcutta (run by the newly formed National Council of Education and started largely with the munificent gifts of Raja Subodh Chandra Mullick), which later evolved into the present-day Jadavpur University. Bengal National College itself was a response to the Government’s increasing repressive measures towards educational institutions following the Universities Act of 1904 which threatened disaffiliation of a number of private colleges, the Carlyle Circular which prohibited students’ participation in politics, and the general atmosphere following the partition of the province.

Yoga And Spiritual Experiences

While his friend Deshpande had been trying hard to get him interested in yoga, Aurobindo, thinking that it necessitated a retreat from the world, initially did not show much interest. He did eventually, around 1904, start some breathing exercises (Pranayama), guided by some tips from his engineer friend Deodhar. He practiced this for hours together, and found his mental and creative powers undergoing an upsurge as a result of this discipline.

During the Baroda years, he had some profound experiences at different times which he later recounted. Once while going in his carriage, he had a miraculous escape. He felt a luminous Divine Being emanated from within him, and taking control of the situation, saved him. He also had an Advaitic experience of oneness at the Takht-e-Suleiman (Hill of Shankaracharya) during his visit to Kashmir with the Maharaja. Another experience was in a Kali temple near Chandod when he felt the divine presence in the deity and pervading the whole place.

While he did not take up any formal discipleship, he was definitely inspired by many yogis he came in touch with. He was particularly struck by a yogi who lived on the banks of the Narmada, Swami Brahmananda, who was said to have been well past 100, and in perfect health. Later still, he received lessons from Vishnu Bhaskar Lele, a Maharashtrian yoga teacher. That too happened in Baroda but during the time when he visited from Calcutta in January 1908. He was by then a celebrated national leader, having ignited the national mind through the pages of Bande Mataram.

His Last Visit to Baroda

Returning from Baroda to Calcutta in June 1906, Aurobindo had immersed himself in the vortex of politics by taking charge of Bande Mataram along with his duties at the National College. BandeMataram had been started by Bipinchandra Pal but later left to Aurobindo’s custody for managing and editing. Aurobindo also helped Barindra and some other young men, including Bhupendranath Dutta (the younger brother of Swami Vivekananda), start the Bengali journal Jugantar for propagating revolutionary ideas. Later Barindra also started a sort of ashrama for revolutionary training (loosely modelled on the Bhawani Mandir idea) at their family garden-house in Maniktala in north Calcutta. The writings in Bande Mataram led to Aurobindo’s arrest in August 1907 but he was immediately released on surety and subsequently acquitted.

Aurobindo attended the Congress session at Surat which saw a fierce split between the Extremists (Nationalists) led by Tilak and the Moderates. Following this, he visited Baroda one last time in January 1908. His carriage was pulled by the students of Baroda College. He delivered inspiring lectures in Baroda. But this visit was also significant because he spent a number of days in intense yoga under the guidance of Vishnu Bhaskar Lele at the house of his friend, Barrister Mazumdar.

During this time he lived in complete privacy immersed in spiritual practice. Upon leaving Baroda, he gave many lectures in Bombay and Poona, where he felt the Divine Voice within him expressing itself. In February, Aurobindo left for Calcutta and then came the dramatic period which saw him arrested and imprisoned for one year in the Muzaffarpur Bomb Conspiracy case along with Barindra and many others. His fate hung in uncertainty but he experienced a perfect calm within.

The whole episode was a remarkable saga, full of dramatic elements – the martyrdom of Khudiram Bose and Prafulla Chaki, assassination of the official witness Narendra Goswami in prison, the spirited enterprise of the defence lawyer Chittaranjan Das (later the nationally venerable Deshbandhu), and the divine providence that the judge in the case, Charles Porten Beachcroft, turned out to be a contemporary of Aurobindo from Clare College at Cambridge who knew him from those days.

Besides, there was the all-important inner metamorphosis that Aurobindo underwent during his days at the Alipore Jail which transformed him with such entirety that he subsequently left his field of action to take up the life of retired contemplation and deep spiritual practice. Aurobindo was released amidst much drama while Barindra was given a death sentence, later changed to transportation for life. Barindra spent the next 12 years in the Cellular Jail in the Andamans and was released after a general amnesty.

After his release Aurobindo spent less than a year in Calcutta, editing his newly started journals Karmayogin (in English) and Dharma (in Bengali). Suspecting a possibility of another arrest he left for the French colonies of Chandernagore and then to Pondicherry, to spend the remaining four decades of his life there.

Sri Aurobindo really began to discover the soul of India once he arrived in Baroda. In the process, he eventually found his own soul, his destiny.