The last two districts in Madhya Pradesh that Narmada flows through are those of Alirajpur on the northern banks, and Barwani on the southern. Before that, as mentioned earlier in this series, for quite some distance the river serves as the boundary between Dhar and Barwani districts. After that, for 40 km it serves as a boundary between Maharashtra and MP – between Alirajpur on the northern banks and Nandurbar in Maharashtra on the southern banks.

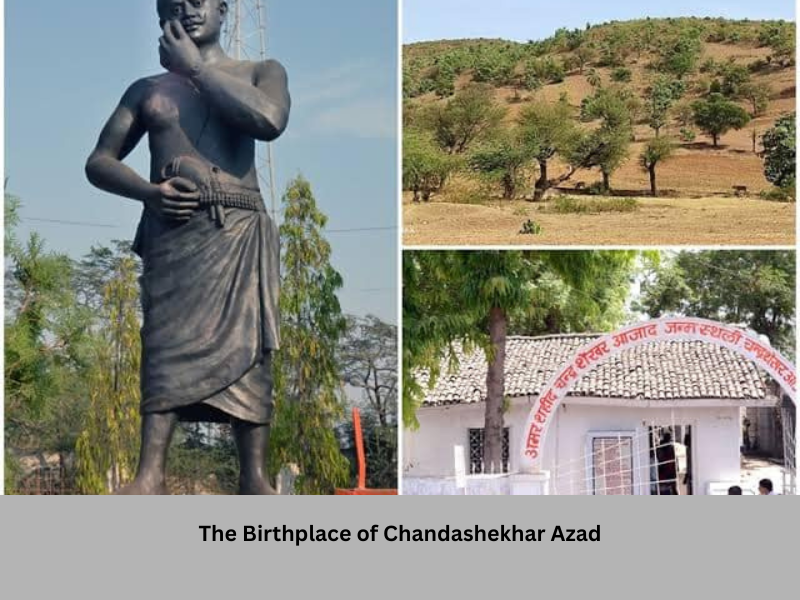

Very near to the Narmada in Alirajpur district is the small village of Bhabhra, which is, something not widely known even to people in MP, the birth place of the iconic revolutionary Chandrashekhar Azad (born Chandrashekhar Tiwari) of the Hindustan Socialist Republican Association who passed away at the age of 24 at Alfred Park in Allahabad, famously taking his own life with the last bullet in his possession when cornered by the police. The village has now been named Chandrashekhar Azad Nagar.

A scenic place on the northern banks is the Hathni Sangam where the Hathni river meets Narmada near Kakrana in Alirajpur district just before Narmada leaves its state of origin.

This entire area is predominantly tribal and the major tribal community in the region is the Bhil community. The Bhils are the third biggest tribal community in the country after the Gonds and the Santhals. Other than the Bhils, other sub-groups like Bhilala, Barela, Naik, Mankar, and Pateliya are also usually clubbed in the larger tribal community of Bhils.

The Bhils are mainly in the western part of the country – in parts of MP, Gujarat, southern Rajasthan and north-western Maharashtra. There had also been a sizeable community of Bhils in the Sindh region (now in Pakistan) but they have now been largely dislocated.

Alirajpur and Barwani are themselves newly carved out districts – Alirajpur from the Jhabua district and Barwani from Khargone. Among all the 52 districts in MP, Jhabua and Alirajpur are the two having the highest tribal community percentage, both with more than 85 percent. Barwani has about 63 percent tribals and Dhar about 56 percent. On the eastern part of the trajectory of Narmada we had Dindori and Mandla being tribal-majority districts and towards the western end in MP is this Bhil country. These districts are without doubt among the poorest regions not only in MP but in the whole country.

Barwani and Alirajpur districts and even parts of Dhar district have come under the backwaters of the Sardar Sarovar Dam. Barwani town is almost on the banks of Narmada. It was one of the several princely states in this part of MP. It had a magnificent ghat called the Rajghat which for most months of the year gets submerged in the backwaters of the Sardar Sarovar Dam. Near Rajghat – a portion of Mahatma Gandhi’s ashes was mingled in the Narmada waters. A few miles after Barwani is a prominent Jain pilgrim centre called Bawangaja which is atop the Satpuras. One has to take a long flight of stairs to reach the summit.

After this, on the southern side, starts one of the most challenging tracts in the Narmada Parikrama trajectory – the Shoolpani Jhaadi. About 130 km in stretch, it interestingly falls in all the three states that Narmada flows in – that is MP, Maharashtra, and Gujarat. It is named after the ancient Teertha of Shoolpaneshwar Mahadev located at the western end of this area. The Shoolpaneshwar temple, which was in the initial part of the river as it entered Gujarat, has also got submerged in the dam project, though a new temple complex has been built opposite to Kevadiya where the ‘Statue of Unity’ as come up.

For some distance the Narmada flows as the boundary between MP and Maharashtra and hence Parikramavasis have to walk on the southern banks through in Maharashtra. Small villages like Keli and Pipalchopani are located here. This area, which is part of the Khandesh region of Maharshtra, in the present day Nandurbar district, was most known among the Parikramavasis for being ambushed and looted by the locals. A little southward is the scenic forest reserve of Toranmal, located in the Satpuras, at a height of about 3500 feet. It has a famous temple dedicated to Gorakhnath where thousands of persons visit during Mahashivaratri.

This entire zone, spread over MP, Maharashtra, and Gujarat – was an area where in the past the local tribesmen took away everything from the Parikramavasis, taking all their belongings and reducing them to bare minimum clothing. This was so regular and certain that it was considered as an essential ritual of the ‘Narmada Parikrama’ where one’s forbearance and detachment to possessions met the ultimate test. Any person who embarks on the highly exacting Narmada Parikrama is sure to have heard a lot of stories that add to the mystique of the Shoolpani Jhadi.

The situation has now changed in recent times with a little improvement in economic condition of the local communities, and also many arrangements like Anna-kshetras (meal-houses) for the Parikramavasis, like those started by highly regarded saint and expounder of Srimad Bhagwatam – Sri Dongreji Maharaj and by Swami Lakhan Giri Maharaj. Several others have come up in recent decades at different places in the Jhadi. This has made things comparatively easier for the Parikramavasis as compared to how it was before. But walking close to the river remains as daunting a task as before. If one chooses to take the road the route becomes much more long.

There are several scholars who claim that the condition of the Bhils in the region had worsened over the last three centuries or so. The Bhils were traditionally a community that practiced shifting cultivation and suffered massively when their lands were encroached first due to the neighbouring royals and chieftains who had themselves got marginalised in the Mughal expansionist period, and later from the Maratha rule in the region from 1730 onwards. Lastly, and most severely, their situation, which had never really been much above subsistence levels, was further reduced to abject penury during the British rule.

It should not be imagined that the situation of the Bhils through the preceding centuries was similar to this. There is evidence that they defended themselves well against the challenges of even mighty empires like the Guptas. Known for their archery skills even Maharana Pratap is said to have inducted a substantial number of Bhils in his force during his encounters with Akbar’s forces. But as times changed their bow and arrow could not match the advanced arms and techniques of their adversaries. This marked the starting of continuous impoverishment of the Bhils with the communities being pushed into the forested and often uncultivable lands in the Vindhyas and Satpuras on either side of the Narmada.

The shifting cultivation practice was brought to an end, and a highly oppressive tax administration left them hand to mouth and even, perhaps for the first time in their history, making them fall prey to debt financing with a network of ‘Sahukars’ (moneylenders) who had settled in smaller towns in the region. The development of railways and increasing demands of industrialisation in the second half of the nineteenth century meant huge claims on the forests in the Vindhyas and Satpuras, and the virtual autonomy that the tribesmen had thus far enjoyed in their natural habitats became further strangulated.

There are scholars who have forwarded the idea that the practice of briganding and waylaying by the Bhils was hardly aimed at looting for gains but in fact with the purpose of stamping their claim on and keeping a guard over their already diminishing homelands. The idea of dispossession and vulnerability had gradually become indelibly entrenched in the community psyche.

Even after independence, the poor literacy rates and consequent lack of awareness of their rights meant that the Bhils failed to take any significant advantage of the enabling features that welfare framework of the Indian State could have potentially provided them with. Even now Alirajpur district has a literacy rate of 37 percent- lowest among all the 55 districts. There used to be very low voting in first few decades following the Independence. The region was almost cut off from rest of the country. Scholar-activist Rahul Banerjee cites an instance that even relatively aware opinion-makers in the region did not come to know of an event like the assassination of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi for almost a week simply because there was no mode of communications in form of newspapers or radio, let alone television, even in the mid-eighties.

There has been considerable material in form of stories and songs present in the Bhil community that recount various incidents and themes of their oppression and dispossession. Many of them deal with the moneylenders, traders and hoarders, contractors, forest guards, and police who to the Bhil represent faces of a machinery that has kept them oppressed. Since the starting of modern activist movements after independence, there has come into being a body of protest songs too that often make cultural references to earlier protest icons like Bhima Naik, Tantiya Bhil, Chhitu Kirat etc.

Mama Baleshwar Dayal

A much forgotten figure even in the state of Madhya Pradesh is that of Baleshwar Dayal, who was once a Gandhi-like figure in these areas. Born in 1905 in Etah district of present day Uttar Pradesh, Dayal had relocated to central India as a teacher. In 1931 he paid a visit to Chandashekhar Azad’s mother at Bhabra and was moved to do something for the tribesmen living in the region. He soon took the job in a school run by Christian Missionaries in Thandla town. In a few years he started a small ashram at village Bamaniya in present day Jhabua district. He was active in the Freedom Movement and the National Congress, and organised his ashram on lines of similar rural ashrams run on Gandhian principles.

In due course Dayal started a number of schools. He launched several movements before and after the independence directed against the oppressive and exploitative forces that the Bhils were continuously subjected to. The Bhils were made to do ‘Begaar’ – forced unpaid labour by the local royals. A movement was launched successfully against this. Dayal also launched campaigns advancing the rights of the tribal communities over the forests. Dayal also did a massive campaign of getting Bhils get rid of alcohol in their day to day life. To get the Bhils adequate respect by other sections of the Hindu society, Dayal with the support of Sankaracharya of Puri, arranged for their ‘Upnayan Sanskar’ and many started wearing the ‘Yagnopaveet’. In the times of polarised ideological views that followed later it is only expected that the last act has come to be seen as controversial by many sections as an endeavour of ‘mainstreaming’ the tribesmen in the traditional framework of Hindu society.

After independence Dayal joined the Socialist Party founded by Jayprakash Narayan which later went through many avatars like the Praja Socialist Party, Samyukta Socialist Party, Socialist Party of India, and also a part of the Janata Party umbrella in 1977. In addition to the redoubtable JP, it had at various points of time, stalwarts like J.B. Kriplani and Dr Ram Manohar Lohiya as leaders. Dayal had huge following and much like Tantiya Bhil was called Mamaji. The activist streak among Dayal’s followers became markedly forceful with insistence on fulfilment of rights that the tribal citizenry had been guaranteed by Constitution and the regimes in power. Along with his followers Dayal had occasions to be jailed even after independence – he had of course enjoyed that privilege during the British times too. These activists distinguished themselves by wearing red caps, as opposed to the white caps of the Congressmen, and the movement came to be known as the ‘Lal Topi Andolan.’

For a time it had impact in Bhil dominated areas of Banswada district in Rajasthan and Ratlam and Jhabua (which then included Alirajpur) in MP and even got notable electoral success. Several among Dayal’s protégés made it to the state legislative assemblies in MP and Rajasthan. Dayal himself had been a member of the Rajya Sabha in the late seventies. He continued to be based in his village ashram at Bamaniya and lived an austere life of a Gandhian till his death in 1998. It is said that he refused any medical treatment in any private hospital that was naturally not affordable to a common person in his region.

The activist edge in the movement had slowly lost steam, in Dayal’s own lifetime itself, as many leading faces in the movement in course of time became part of the establishment itself while others who tried to continue the struggles were crushed or eventually got fatigued. But Baleshwar Dayal’s contribution to struggles, constructive work as well as political awareness of the downtrodden Bhils is something which deserves to be better recorded for posterity.